Background Evidence Review

Problems, Opportunities and Constraints

Problems

Three key problem groups were determined through a literature review, discussions with stakeholders, and analysis. These problems have been defined as:

High and Increasing Demand for Car Travel:

- Increases in vehicle kilometres between 2009 and 2019 disproportionally higher than population growth (Source: A route map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030, Transport Scotland, January 2022).

- Post COVID-19 recovery of car traffic to much stronger than for public transport (Source: COVID-19 - Scotland’s transport and travel trends during the first six months of the pandemic, Transport Scotland, January 2021).

- 65% of car kilometres travelled are on the longest 20% of journeys (over 19.62km) (Source: Scottish Household Survey – Additional Processing by Keith Hoy, 2022).

- Transport is the largest emitter of CO2 emissions and targets will not be met unless there is a reduction in vehicle kilometres and demand for car use (Source: Professor David Begg & Claire Haigh, Re-charging Britain’s Road Policy, 2021).

- Negative economic impact of congestion.

- Disruptive technology such as MaaS and Autonomous Vehicles.

Decreasing Revenue from Fuel Duty and Vehicle Excise Duty (VED):

- Due to freezing of rates since 2010 and trend towards more efficient vehicles – decreasing revenue will only accelerate as sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles is phased out by 2030 (House of Commons Transport Committee, Road pricing Fourth Report of Session 2021–22).

- Though VED will apply to Electric Vehicles (EVs) from 1 April 2025, no mechanism exists for taxing the electricity used for vehicle charging.

- Falling revenue will reduce the taxation intake, impacting all areas of public spending.

Transport Inequality:

- Lack of alternatives in some areas puts people in a situation of forced car ownership (Source: Curl, A., Clark, J., & Kearns, A. Household car adoption and financial distress in deprived urban communities: A case of forced car ownership? 2018 Transport Policy, 65, 61-71).

- Those on higher incomes contribute more to the total car kilometres than those on lower incomes (Source: Transport Scotland, Annex for a route map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030: Reducing car use for a healthier, fairer, and greener Scotland. 2022).

- Nearly 30% of households have no access to a car and for the lowest income households this rises to 60% (Source: Transport Scotland, Scottish Transport Statistics 2015, Table 1.20.)

- Rural areas have a higher car mode share and people make longer trips than those in urban areas (Source: TForward, Delivering Better Roads – Wolfson Economics Prize Submission, 2017).

- For people with a long-term health problem or disability, 46% have no access to a car (Source: Scotland’s Census. Table LC3405SC - Car or van availability by long-term health problem or disability by sex, 2011).

- Strong links between road traffic accidents and areas of deprivation, with children in Scotland’s poorest communities at three times higher risk of death or injury while out walking or cycling (Source: Quayle, Investing in cycling to tackle transport poverty and promote equity. The Scottish Transport Applications and Research (STAR) Conference, 2019.)

Opportunities

The review also identified a number of opportunities for implementing a TDM scheme in Scotland in the present context:

- Changing attitudes around climate, sustainability and data sharing.

- Low uptake of EVs to date – making it easier and more acceptable to create a new charge applicable to EVs prior to mass ownership.

- Political Context – reducing car kilometres is a central Scottish Government policy.

- New Technology – advances in in-vehicle telematics and mobile apps for administration.

Constraints

Governance represents the main constraint around implementing TDM measures in Scotland. Currently powers over motoring taxation are reserved to the UK Government while powers relating to road user charging on local authority roads and parking is devolved to local authorities (Source: Legislation.gov.uk, Acts of the Scottish Parliament, Transport (Scotland) Act 2001). The Scottish Government only has direct control over the trunk road network, through its agency Transport Scotland. This limits the influence the Scottish Government can have on policy making and implementation in these areas. A further constraint is the timescales of net zero targets and the 20% car kilometres reduction target, meaning any proposal should be operating effectively by 2030 at the latest.

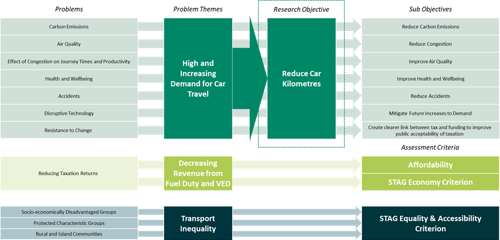

The problems identified were used to validate the research objective as set in the Climate Change Plan of reducing car kilometres by 20% by 2030. Figure 2‑1 below shows the alignment between identified problems, the research objective and other assessment criteria.

Research Objective

The problems identified were used to validate the research objective as set in the Climate Change Plan of reducing car kilometres by 20% by 2030. Figure 2‑1 below shows the alignment between identified problems, the research objective and other assessment criteria.

The research objective is well aligned to addressing the problem of high and increasing demand for car use and achieving the research objective will directly link to improvements in the individual problems identified, such as high carbon emissions, air pollution, congestion and accidents.

The problem themes of ‘Decreasing Revenue from Fuel Duty and VED’ and ‘Transport Inequality’, while important factors in the success of any proposed TDM measures, have not been developed into research objectives. Impacts against these problem themes will be assessed through existing STAG and Deliverability criteria and highlighted throughout the assessment as critical success factors.

Like all Transport Planning Objectives, the research objective as provided in policy documents has been strength tested through SMART principles:

- Specific: The objective relates to contributing towards a key government target of a 20% car use reduction compared to 2019 levels.

- Measurable: This metric is published annually by Transport Scotland in Chapter 5 of the Scottish Transport Statistics.

- Achievable: It is believed that the target, though ambitious, is achievable. Specific steps to be taken to meet the target are outlined in ‘A route map to achieve a 20 per cent reduction in car kilometres by 2030’.

- Relevant: The objective addresses problems relating to high and increasing demand for car travel as outlined in 2.1.1.

- Time-bound: A 2030 date for the target to be met is linked directly to meeting the targets of the Climate Change Plan pathway to net zero by 2045.

Literature Review

The literature review has drawn on extensive range of demand management typologies to understand their potential impact on reducing vehicle kilometres and other impacts within the Scottish context. This section summarises the key findings from the literature review for each TDM typology identified.

Cordon and Area Based Charging

In London there has been a successful area based charge in place since 2003. This scheme was implemented by TfL, a public agency responsible for all of the city’s transport network, that developed a focused business case which led to early commitment for funding and resource. The zone where the charge applies is relatively small central area of the city. The London scheme uses ANPR cameras as enforcement, which require significant capital investment to install and a large back office requirement for successful operation. It has had the following impacts:

- Reduced the volume of traffic entering the charging zone by 31% (Source: Pricing for Prosperity – Wolfson Economics Prize Submission, 2017). However, its impact has diminished over time, with a particular exemption for taxis resulting in more congestion and reducing bus patronage as apps such as Uber have grown (Source: Badstuber, Nicole, London congestion charge has been a huge success. It’s time to change it, The Conversation, 2018 (updated 2019).

- Net income of £156 million, with 51% of this spent on collection cost. Revenue is relatively small compared to the annual TfL streets budget of £725 million (Source: Silviya Barrett, Martin Wedderburn and Erica Belcher, Green Light: Next Generation Road User Charging for a Healthier, More Liveable, London).

- Positive environmental impacts with NOX and PM10 decreasing by 18% and 22% respectively, and greenhouse gas emissions reducing by 16% (Source: Centre for Public Impact, London’s Congestion Charge, 2016).

- Between 40 and 70 per cent fewer accidents which resulted in personal injury within the zone (Source: Centre for Public Impact, London’s Congestion Charge, 2016).

- Economic benefits for businesses and freight operators as better network performance resulted in journey time reductions (Source: Andrea Broaddus, Michael Browne, Julian Allen, Sustainable Freight: Impacts of the London Congestion Charge and Low Emission Zones, Transportation Research Record, 2015).

A cordon charge in Milan saw a 29% reduction in car trips, and when the scheme was temporarily halted a two month spike in traffic occurred (Source: Silviya Barrett, Martin Wedderburn and Erica Belcher, Green Light: Next Generation Road User Charging for a Healthier, More Liveable, London). The scheme also demonstrated how implementing vehicle restrictions in historic city centres can have marked benefits for pedestrian and cyclists and improve the economic vibrancy of the city centre.

In recent times, existing area-based schemes have looked towards replacing conventional ANPR enforcement systems with more technological solutions which allow more responsive and tailored charging regimes to be implemented, which incorporate distance-based charging. Brussels has begun piloting an app-based charge within the greater Brussels area, which provides real time price information and links users to multimodal alternatives (Source: Brussels SmartMove (2023)). Research has also been undertaken into a similar system to replace the existing network of infrastructure used to enforce the congestion zone in London (Source: Silviya Barrett, Martin Wedderburn and Erica Belcher, Green Light: Next Generation Road User Charging for a Healthier, More Liveable, London). Such app-based systems provide the opportunity for greater levels of feedback and integration with other initiatives such as smart ticketing and mobility as a service. This approach could also significantly reduce running costs, compared to systems solely based on ANPR enforcement.

The Transport (Scotland) Act 2001 provides local authorities discretionary power to implement local road user charging schemes, however, additional primary legislation would be required to implement a road user charge on trunk roads. Public appetite for congestion charging has, so far, only been fully tested once in Scotland, and not in the recent past. In 2005, in Edinburgh a cordon scheme was proposed, voted on in a referendum and rejected. There are many factors identified in the rejection of the Edinburgh’s congestion charging plans, including perceptions of unfairness and a lack of clarity on what the revenue generated would be used for. There is evidence that public acceptance increases post implementation of a scheme – in London prior to implementation support for congestion charging was 40%, which rose to 59% post implementation (Source: Pricing for Prosperity – Wolfson Economics Prize Submission, 2017).

Research for a scheme in Wellington, New Zealand found cordon charging targeted on trips to a Central Business District is more likely to affect higher income households relative to low income households (Source: NZ Transport Agency, Social and distributional impacts of time and space-based road pricing, 2019). Additionally the London area based charge includes exemptions for various vehicle types and users such as blue badge holders, vehicles with nine or more seats, electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and a 90 per cent reduction for residents within the zone (Source: TfL, Discounts and exemptions, 2022).

Distance Based Charging

Distance based charging, with a variable parameter for vehicle characteristics, can be an effective way to reduce air pollution. Similarly, if the charge varies with time of day, this could reduce congestion at peak times and more accurately account for the external costs of driving. Dynamic pricing can also optimise the scheme to make it more equitable (Source: Scott Corfe, Miles Ahead- Road pricing as a fairer form of motoring taxation, The Social Market Foundation, 2022).

In the UK distance-based charging was proposed in 2007 as a replacement to existing motoring taxes. This would have used in-vehicle telematic technology such as Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) to monitor the distance driven (Source: Department for Transport, Feasibility study of road pricing in the UK, 2007). The majority of fleet operators in the UK now employ telematics tracking in their vehicles to track fuel efficiency, accidents and vehicle health (Source: RAC, Telematics Report, 2016). Some vulnerabilities remain with GNSS technology which may allow the system to be bypassed. GNSS enforcement would therefore need to be supported by a secondary system, such as ANPR. Any mandated use of GNSS tracking is likely to receive significant public opposition due to privacy concerns. A survey of 3,000 people found that, even among supporters of road user charging, 48% are opposed to having a mandatory tracking device installed in vehicles (Source: Scott Corfe, Miles Ahead- Road pricing as a fairer form of motoring taxation, The Social Market Foundation, 2022). Conversely, evidence used in the feasibility study for the 2007 UK nationwide scheme found 62% did not consider privacy concerns with satellite technology a major issue (Source: Department for Transport, Feasibility study of road pricing in the UK, 2007).

A voluntary approach, using an app-based system of charging is currently being trailed in Brussels and offers a test-case for how tracking of individual milage could be introduced in a way which could engender public support by incentivising alternative forms of transport (Source: Brussels SmartMove (2023). Similarly, Oregon’s OReGO scheme was launched in 2015 on a voluntary basis, allowing motorists to pay a per mile charge instead of fuel tax. Private sector partners provide the platform for in-vehicle devices and payment (Source: Silviya Barrett, Martin Wedderburn and Erica Belcher, Green Light: Next Generation Road User Charging for a Healthier, More Liveable, London).

A model of a distance based charge for Greater London resulted in fewer trips from outside existing charging zones but actually increased car trips inside existing charging zones given the short nature of these trips results in the distance charge being lower than the existing area based charge (Source: Silviya Barrett, Martin Wedderburn and Erica Belcher, Green Light: Next Generation Road User Charging for a Healthier, More Liveable, London).

Quantitative analysis of a distance based road pricing scheme for Auckland, New Zealand found lower income households, households with children, and single parent households were likely to experience the largest financial burden, relative to income of a scheme, with the magnitude of impacts varying by location (Source: Green Light: Next Generation Road User Charging for a Healthier, More Liveable, London).

A nationwide distance based charge would need to take into account the differences in transport availability between urban and rural areas for the scheme to be equitable. A study in Serbia concluded that a universally applied TDM policy across a country with a mix of urban and rural areas would “deepen material and transport deprivation” (Source: Jadranka Jovia, Biljana Rankovic Plazinic, Transportation Demand Management in Rural Areas, 4th International Conference “Towards a Humane City”, 2013). In Ireland the Five Cities Demand Management Study did not recommend a simple per km charge because the flat rate would be unfair on rural areas where driving distances are greater and these is less availability of alternatives (Source: Department for Transport Ireland, Five Cities Demand Management Study, 2021).

Tolls

Historically tolls have been introduced on particular infrastructure to recoup the costs of construction or contribute to the maintenance budget. Their effectiveness at reducing car kilometres can be questioned as evidence from the Mersey Tunnels in Liverpool show similar car mode shares for journeys between the Wirral and Liverpool to un-tolled journeys such as Fife to Edinburgh. (NOMIS, 2011) (Source: Nomis: Official Census and Labour Market Statistics, Location of usual residence and place of work by method of travel to work, 2011). There is also potential for diversion and displacement of traffic to unsuitable local roads or longer distance routes to avoid the charge.

Parking

Using parking as a TDM measure can be done in multiple ways including traditional parking charges at destinations, workplace and retail parking levies, where businesses are charged per space they supply to their employees, or customers and residents parking permits.

Parking enforcement is controlled by many local authorities in Scotland and for some raises revenue. Edinburgh and Glasgow bring in £12.2 million and £2.7 million respectively from annual parking charges, while 71% of other local authorities in Scotland enforce parking at a loss (Source: Transport Scotland, Decriminalised Parking Enforcement: Local Authorities Income and Expenditure: 2020-2021, 2021). Recent polling suggests any increase in parking charges would be heavily opposed by the public (Source: Institute for Public Policy Research – Fair Transition Unit, Fairly reducing car use in Scottish cities - A just transition for transport for low-income households, 2022).

Workplace Parking Levies (WPL) can be effective at encouraging behaviour change, both for employers who are more likely to relocate businesses to locations with better public and active travel links, which makes providing less parking acceptable, or employees if the charge is passed on to them. In Nottingham 80% of employers pass the charge on to employees and the levy has had the following impacts:

- 40% mode shares for public transport, with 50% of people citing the WPL as the reason for their reduced car use (Source: Simon Dale, Matthew Frost, Stephen Ison, Lucy Budd, The impact of the Nottingham Workplace Parking Levy on travel to work mode share, Loughbourgh University, 2019).

- Nottingham has raised revenue to fund significant public transport improvements (Source: Sustrans, Sustrans Response to the Transport (Scotland) Bill – Workplace Parking Levy Amendments, 2019).

- The city has been able to meet air quality obligations without the need for a clean air zone (Source: Fleet News, Nottingham's parking levy provides air quality advantage, roundtable reveals, 2018).

- Job creation in the city has occurred at a faster rate than comparable cities (Source: Nottingham City Council, Workplace Parking Levy (WPL) Evaluation Update – April 2016).

- £25.3 million revenue generated with 5% administration cost (much lower than comparable cordon and area based charges) (Source: World Wildlife Fund, International Case Studies for Scotland’s Climate Plan: Workplace Parking Levy, Nottingham, UK, 2017).

A WPL is also considered a progressive measure as the majority of people on low incomes do not drive to work and benefit from improved public and active transport the WPL helps to fund (Source: Sustrans, Sustrans Response to the Transport (Scotland) Bill – Workplace Parking Levy Amendments, 2019). Dynamic parking charges could disproportionally impact those on lower incomes as this group has less potential to retime their journeys due to less work flexibility (Source: Victoria Transport Policy Institute, Parking Pricing, 2019).

A Retail Parking Levy was proposed in the New Future for Scotland's Town Centres review for out of town sites to encourage high street revitalisation and provide revenue for local authorities to improve public and active travel. Legislation does not currently exist to enable local authorities to implement such a scheme. Current practice of providing free parking at retail sites is highly regressive as all customers ultimately pay for the provision, while it only benefits those who drive to the sites (Source: International Transport Forum, Reversing Car Dependency: Summary and Conclusions, ITF Roundtable Reports, No 181, 2021).

Taxation

While the policy areas of road maintenance and usage is fully devolved to the Scottish Government, existing forms of motoring taxation, namely VED and Fuel Duty are reserved to Westminster. Fuel Duty, if used correctly, could be an effective TDM tool: in Beijing a moderate increase in fuel prices led to a 7% reduction in traffic volume (Source: Ping Qin, Xinye Zheng, Lanlan Wang, Travel mode choice and impact of fuel tax in Beijing, Environment and Development Economics, Volume 19, Issue 1, pp 92-110, 2014). However, in the UK levels have been frozen since 2010 and will not be compatible with the trend towards cleaner and zero emission vehicles, with evidence suggesting revenue from fuel duty could fall to near zero by 2050 (Source: Pricing for Prosperity – Wolfson Economics Prize Submission, 2017). An alternative could be a surcharge on electricity used to charge Electric Vehicles, however this would involve significant costs of new infrastructure to detect what household electricity is being used for. Additionally this could encounter significant public acceptability issues as owners of EVs have benefited from paying no tax on their motoring, and increasing the cost of running an EV could have a negative climate impact by slowing the transition to cleaner vehicles (Source: TForward, Delivering Better Roads – Wolfson Economics Prize Submission, 2017).

An added complication to using existing motoring taxations as a wider TDM tool is the powers over these taxes are reserved to the UK Government and creating new taxes or surcharges in these areas may not be within the devolved competency of the Scottish Government. Additionally existing motoring taxes are perceived as among the most unfair and increasing these will be very unpopular (Source: Stuart Adam & Rebekah Stroud, A road map for motoring taxation, 2019).

Fuel duties are not well targeted to areas where air pollution is a particular problem, as drivers pay the same regardless of where they drive (Source: OECD Taxation Working Papers No.44, Taxing vehicles, fuels and road use: Opportunities for improving transport tax practice, 2019). Additionally they impact low-income households more than high incomes, given low income households tend to own older and therefore more highly polluting vehicles (Source: Mirrlees Review, Tax by Design, 2011).

Low Emission Zones

Low Emission Zones (LEZ) have experienced a high profile in recent years, given they have been introduced in four Scottish cities in May 2022, with enforcement starting in Glasgow in 2023 and the other three cities in 2024. They utilise similar technology to area based charging, as cameras are used to monitor number plates and ensure only vehicles compliant with certain emission standards are allowed within the zone. Scottish LEZs do not operate as per the typical charging LEZs elsewhere – instead of paying a low daily charge to enter, non-compliant vehicles incur a significant penalty charge notice. This should act as a deterrent and together with the LEZ Support Fund is expected to encourage modal switch.

While LEZs could be considered a ‘springboard’ towards further interventions such as cordon or area based road pricing, their efficacy as a tool for reducing the amount of car kilometres is uncertain. While compliant vehicles have no disincentive for use, owners of noncompliant vehicles are more likely to change their travel behaviour (Source: Tarrino-Ortiz, J., Gomez, J., Soria-Lara, J.A. and Vassallo, J.M., 2022. Analyzing the impact of Low Emission Zones on modal shift. Sustainable Cities and Society, 77, p.103562).

Road-space Rationing

Road Space rationing is a method for managing transport demand by restricting access to the road network for different users on different days. Most common is alternate day driving, where only certain cars are allowed to use the road network on certain days or times. Common examples include even-odd number plate driving days, where around half the registered vehicles in a given area are banned from the road network on alternating days. Schemes of this nature have been introduced in cities such as Mexico City, Beijing, and Paris.

However, in all these cases, road space rationing was introduced to curb air pollution problems, and sometimes only introduced temporarily while air pollution was at its most dangerous levels (Source: Chilcott, S, Parisian’s Ponder Road Space Rationing, 2014). Additionally schemes of this nature can be very inequitable, favouring those wealthy enough to purchase two vehicles which ultimately leads to the road space taken up by vehicles increasing (Source: Gajurel, A, Road space rationing is not the ultimate solution, Face to Face, 2019). Furthermore, the deterrent for breaking the regulation can be low: in Paris the fine is €22, around £18 and only £8 more than the Daily London Congestion Charge.

Road-space reallocation

Rebalancing of urban living environments away from traffic and towards creating more healthy and liveable places can be achieved by restricting through traffic from residential areas by either physically blocking vehicles (with bollards or one-way streets) or by imposing charges, enforced via cameras. Such area-wide traffic reduction schemes are becoming commonly known as low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs) (Source: Sustrans, What is a low traffic neighbourhood, 2020). Recent meta-analysis of motor traffic changes across 46 LTN schemes in London has demonstrated that LTNs have been successful in reducing car traffic within LTNs without evidence of displacement of congestion onto neighbouring streets (Source: Thomas, A & Aldred, R (2023) Changes in motor traffic inside London’s LTNs and on boundary roads). Other forms of road space reallocation can include reducing traffic lane widths, removing lanes and installing cycle lanes or public transport priority measures. Evidence has shown that reducing road space for private cars can lead to overall and significant reductions in the amount of traffic (Source: International Transport Forum, Reversing Car Dependency: Summary and Conclusions, ITF Roundtable Reports, No 181, 2021). A more recent approach to traffic reduction stemming from similar principles as LTNs are traffic circulation plans, which aim to segment towns and cities and prevent inter urban traffic crossing between segments, forcing them out onto the strategic road network instead. This approach has been successfully adopted in Ghent (Source: Municipality of Gent. The Circulation Plan) and is soon to be implemented in Oxford (Source: Oxfordshire County Council. Traffic Filters). Again, this approach could be implemented physically, using bollards and road closures, or via camera enforcement. As such, the ‘traffic circulation plan’ approach could be considered a variation of the area-based road pricing model but where the boundaries are drawn in segments rather than concentric rings.