Findings

School Visits

This section presents the findings from the school visits. Three rounds of school visits were undertaken in (i) May/June, (ii) October, and (iii) November/December. Each visit comprised a warm-up task with pupils, pupil focus group discussion, and, where possible, an informal teacher interview.

The schools were asked to select a group of seven to eight pupils for the focus groups; preferably made up of pupils in primary five and six (i.e. older pupils who could be present for all visits, noting that pupils in primary seven at the time of the first visits would have left the school by the time of the second and third visits due to the evaluation period straddling two school years). The client requested that the focus groups were made up of pupils who already travel to school actively. In practice, the focus groups varied in size from around five pupils to 20 pupils. In many cases the school focus groups comprised the pupil Junior Road Safety Officers (JRSOs).

The first round of school visits took place between Friday 19th May and Wednesday 7th June 2023 and involved all nine participating schools. The initial focus groups lasted around 30-45 minutes.

The aim of the first visit was to understand the baseline:

- School context and existing initiatives.

- Travel behaviour.

- Attitudes to active travel.

- Road safety awareness.

The second round of school visits took place between Tuesday 3rd October and Friday 13th October. Coylton and Mauchline were not visited due to delays in starting the prize component of the scheme. Reasons for these delays are explored in the following section (School Context) and both schools were visited during the final round of visits. Note that due to the shorter trial period in North Ayrshire, the second visits took place as the scheme was ending and therefore, a third visit was not undertaken to these schools.

The third round of visits took place between Thursday 30th November and Friday 8th December 2023, involving only the East and South Ayrshire schools.

It was requested that the same group of pupils present during the first visits would be in attendance for the second and third visits where possible.

The aim of the second and third round of visits was to understand:

- Any changes in school context that could have impacted effectiveness of the trial.

- Changes in travel behaviour.

- Changes in attitudes to active travel.

- Changes in road safety awareness.

- Opinions on the scheme.

School Context

Various contextual factors potentially affecting the scheme performance were noted during the evaluation. Where possible, at the start or end of each visit, teaching staff were interviewed about existing active travel and road safety initiatives at the school and their own thoughts on the scheme, as well as any other relevant information that they wished to feed back.

It was generally found that each of the schools involved in the trial also participated in a wide range of other road safety and active travel schemes including JRSOs, Bikeability Training, and iCycle. In East Ayrshire, an active travel initiative called Journey to Jupiter, funded by the Climate Change Fund, was launched in September 2023. This project is similar to Trailblazers in its aim to get young people walking to school, in a bid to further reduce carbon emissions in East Ayrshire, while also reducing congestion at school gates and promoting active travel.

The overlap of the Journey to Jupiter scheme with Trailblazers was cited as a barrier to the successful implementation of the Trailblazers project in the East Ayrshire schools. In particular, schools noted that each scheme provided its own format for recording active travel to school, and this resulted in an unmanageable amount of administration for class teachers at the beginning of the school day. This resulted in a delay to the implementation of the scheme at Mauchline Primary School, and the second school visit was not undertaken. However, following discussions with the local authority road safety operative, to clarify flexibility in the recording and reporting of active travel to school and the criteria for prizes, Mauchline Primary School were able to implement the scheme in time for the final round of school visits.

A change in the staff contact contributed to a delay in the implementation of the prize aspect of the scheme at Coylton Primary School, and the second school visit was not undertaken. This was resolved and the scheme was implemented in time for the final round of school visits.

Two reported safety incidents were also anecdotally noted to have perhaps influenced perceptions and behaviours relating to road safety:

- At Forehill Primary School, it was noted that a crossing patrol person was fatally injured in a road traffic accident outside the school a number of years ago. The school has been undertaking extensive work to improve road safety, but this is still considered an ongoing challenge.

- New Cumnock Primary School is located on the A76; a busy trunk road linking Dumfries to Kilmarnock. During the Trailblazers scheme operation there was a road traffic incident on the A76 in New Cumnock involving the fatality of a child.

Experience Travelling to School

During the initial school visits, a map-based task was undertaken whereby pupils were asked to identify road safety concerns around each school. Pupils were given a map showing their school and the surrounding area and indicated the locations of issues of concern. Depending on the size of the group, this was explored either through group discussion or by individually drawing on the maps, and sometimes with input from staff.

Key issues identified included:

- Parked cars around schools, sometimes blocking crossings, junctions, and driveways.

- Speeding traffic.

- Traffic and congestion.

- Vehicles failing to obey the crossing patrol or traffic signals.

- Some issues with maintenance of signs, paths, roadside verges/bushes.

- Lack of crossing facilities.

These issues affected perceptions of safety when travelling to school. In particular, pupils noted difficulties with:

- Crossing the road due to speeding, traffic, and poor visibility.

- Having to walk or cycle on the road to navigate obstructions.

Map outputs informed by the pupil discussions i.e. noting issues of concern by location, are presented in Appendix B.

Where applicable, the mapping task was revisited during the return visits to assess the extent to which previously identified issues still remained. In some schools, including Skelmorlie and Doonfoot, pupils noted that they perceived there to have been some decreases in traffic volumes and on-street parking since the scheme had been implemented, which the pupils felt was due to the Trailblazers scheme leading to an increase in active travel to school. However in other schools, the concerns raised at the first visits were a continuing issue, for example high traffic volumes at Coylton and New Cumnock.

Current Travel Patterns, Experience, and Views

Travel to School

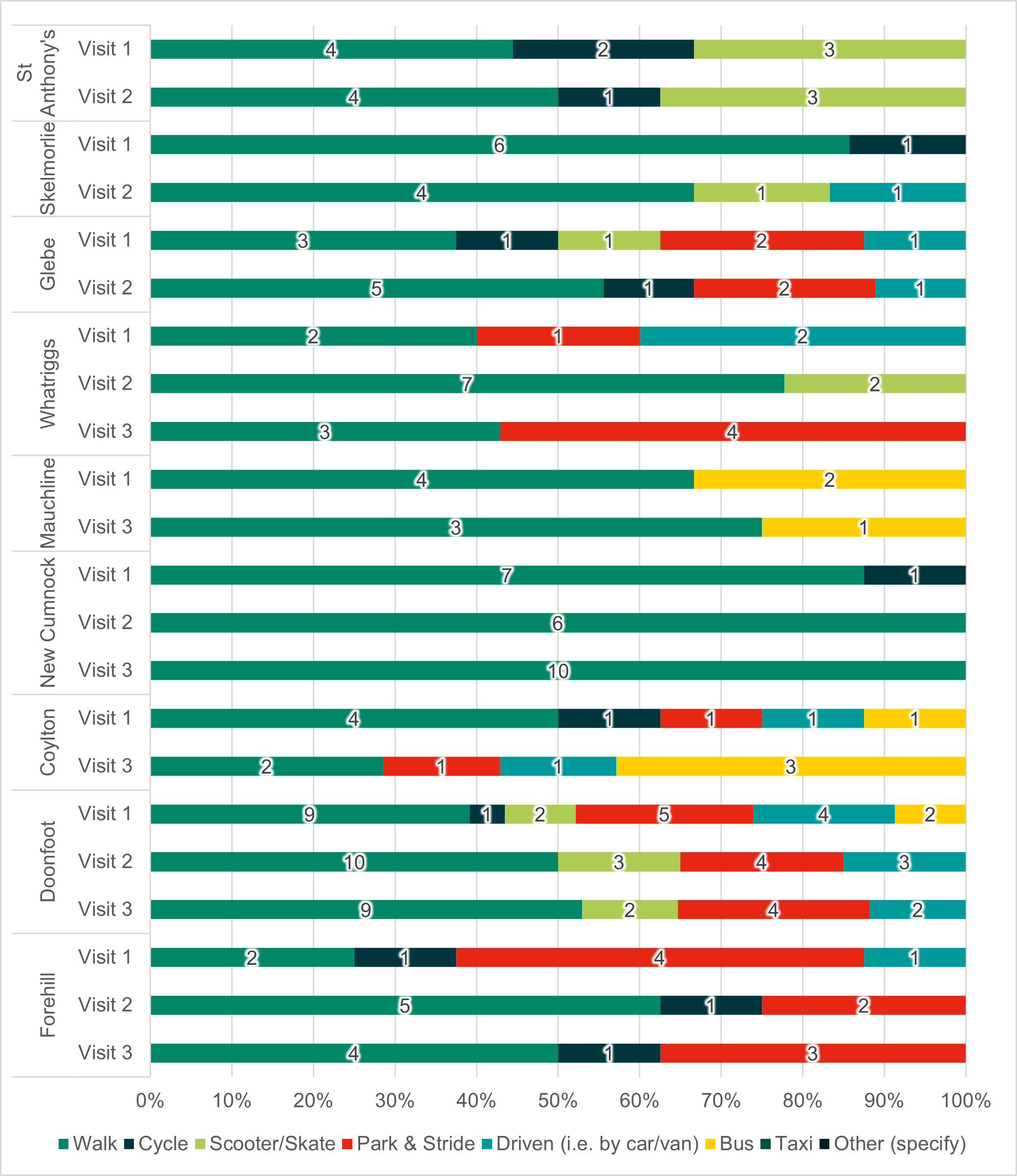

During each visit, pupils were asked how they usually travelled to school. As requested by the client group, the school focus groups were made up predominantly of pupils who typically walked or cycled to school. Due to this, and the small sample size, the data collected is not necessarily representative of each school’s overall travel to school mode share and simply provides some context to the focus group discussion. There was not considered to be significant differences in mode share between the visits.

Pupils who did not travel actively to school were asked why not. During the initial visit, distance from school was identified as the main barrier in Whatriggs, Doonfoot, Mauchline, and Coylton. In Forehill, safety of active travel routes was the main barrier. In Glebe, the main reason for not travelling actively was pupils being dropped off by a parent/carer travelling elsewhere directly from the school. It was noted that 50% of Glebe pupils do not live within the catchment area. Reasons for not travelling actively to school remained largely similar between visits.

Views on Road Safety and Active Travel

To assess perceptions and understanding of road safety and active travel amongst school pupils the pupils were asked for their views on the following statements:

- Vehicle speeds around the school are too fast.

- There is too much traffic around the school.

- Parked cars around the school make crossing the road difficult.

- I feel safe travelling to school.

- I know what the Green Cross Code is.

- I have a good knowledge of road safety skills.

- I know what active and sustainable travel means.

Responses were recorded using a simplified Likert-style scale as follows:

- Agree

- Disagree

- Don’t know

A detailed breakdown of how pupils responded at each school during each visit is presented in Appendix C.

During the initial visits, pupils generally agreed that vehicle speeds around the school are too fast, except in St Anthony’s, Doonfoot, Mauchline and Glebe. In some schools such as Coylton, Skelmorlie, Forehill and Whatriggs, agreement with this statement decreased in the subsequent visits, suggesting some positive impacts from the scheme. However in New Cumnock, perception of speeding increased.

During the initial visits, pupils generally agreed that there is too much traffic around the school, except at Skelmorlie and Coylton. Interestingly, in both Skelmorlie and Coylton agreement with this statement increased in the subsequent visits. Agreement remained similar between visits for the other schools, except for St. Anthony’s where there was a shift from agreement to uncertainty and in Forehill where there was some reduction in agreement with the statement, suggesting some positive impacts from the scheme at Forehill.

During the initial visits, pupils generally agreed that parked cars around the school make crossing the road difficult, except in Skelmorlie. This shifted to disagreement in Doonfoot by the third visit, and there was some reduction in agreement at Forehill and St Anthony’s, suggesting some positive impacts from the scheme at these schools. New Cumnock and Whatriggs saw an initial decrease in agreement before an increase at the final visit, while Coylton and Skelmorlie both saw an increase. This could potentially be due to changes in seasonality.

During the initial visits, pupils in all schools agreed they had a good knowledge of road safety skills. In some schools this increased over the course of the visits, but in others it actually decreased. This reduction could have been due to greater self-awareness as a result of the scheme.

During the initial visits, pupils generally agreed that they feel safe travelling to school, except in Coylton, Forehill, New Cumnock, and St Anthony’s. In several schools there was an increase in agreement in the subsequent visits, suggesting some positive impacts from the scheme, however in Coylton and Glebe there was a decrease, potentially due to improved awareness of the risks or changes in seasonality.

Overall there was some evidence that pupils were feeling safer travelling actively to school following the scheme due to a decrease in vehicle speeds, and in some cases reduced parking around the school.

Impact of the Trial

Scheme Branding and Recognition

To understand the effectiveness of the scheme branding, pupils were asked what the word “Trailblazer” meant to them. In the initial visits, the scheme had not yet been launched, so the responses reflected pupils’ initial thoughts on the word. Some pupils thought of non-transport meanings such as fire, or a brightly coloured vest. Others thought of following a path, moving quickly, or going for a walk. Perhaps extrapolating from some of the other focus group discussion, some pupils thought of safety such as making a trail safer or safety on the roads.

Responses during the return visits suggested awareness of the scheme and its objectives. In addition to the initial themes which came up during the first visit, key thoughts relating to the word “Trailblazer” included safer walking to school; walking, wheeling and cycling becoming a fun experience; Blaze the horse; QR code lamppost wraps; 5/10 minute signs; getting healthier; walking to school more frequently; and being more environmentally friendly.

Views on the scheme

During the first visits, pupils were fairly supportive of the scheme and many felt that it would encourage more walking to school and help make the journey to school more exciting. Some pupils suggested the scheme could lead to more walking in groups. In addition, some pupils believed that the scheme would help to educate pupils and parents/carers on road safety and help the environment as a result of fewer pupils being driven to school. However, some potential risks were highlighted across multiple schools including concern that signs could be vandalised, risks associated with pupils being distracted by their phones and not paying attention to the road, and potential difficulties associated with not all pupils having access to a mobile phone.

Pupils generally thought their parents/carers would also be supportive of the scheme, as they may feel more comfortable about their children walking or cycling to school (either accompanied or unaccompanied), reducing the need for them to drive. However, some pupils suggested that parents/carers may be concerned about their child walking to school unaccompanied, and others felt parents/carers may have security concerns about scanning the QR codes.

Based on the return visits, engagement with the scheme was mixed amongst pupils. Key observations were:

- Some of the schools including Doonfoot and Whatriggs had not launched the prize aspect of the scheme by the time of the second visit. Engagement at these schools was generally lower than at others. However, a significant difference in pupil engagement was observed between the second and third visit, with clear enthusiasm for the prizes. An increase in engagement following the introduction of prizes was also noted at Skelmorlie. Some pupils reported that older pupils in particular were only taking part in the scheme because they wanted the prizes, which demonstrates the success of the prizes as a motivation.

- Some pupils said the QR codes made the journey to school more fun. Although one pupil noted that the QR code just takes you to a website, but it’s the same link every time, so there’s no need to actually scan the code every time – it’s possible to just keep the window open on the phone to see the questions.

- Some pupils were concerned that scanning the code slowed them down on their journey to school or made them late. There were some reports of queues/crowding around the codes.

- Some pupils reported changes in their own travel behaviour, with a shift from being driven to walking, and some reported taking a different route to go past a QR code. Several groups noted a general increase in walking to school.

- In some schools a reduction in traffic was noted, and pupils felt safer travelling actively to school. In Forehill in particular, pupils said they felt safer crossing the road due to the reduction in traffic.

- In New Cumnock there was some uncertainty expressed about which QR codes should be scanned to get to the questions; one pupil noted that they had scanned the lamppost wrap instead of the sticker.

- Coylton ran a ‘Santa Stroll’ walk in December, allowing pupils who normally travel by bus or taxi to get involved in the scheme.

- There was some concern about pupils being left out, particularly those who get a bus or who don’t have a phone or travel to school with parents/carers who have a phone.

- Some pupils said that they suspected others were not always accurately recording their travel to school, to get the prizes. Others suggested that parents/carers were pulling their cars over at the signs on the way to school to allow pupils to scan.

Vandalism was reported to be an issue at some schools, particularly New Cumnock, but also Glebe, Mauchline, and Coylton. This included spray-painting on signs, damage to signs, and removal of signs.

Doonfoot Case Study

At Doonfoot, the JRSOs were asked to speak to other pupils in the wider school and find out what they thought about the scheme. The pupils prepared and administered a short survey, and shared their findings.

One of the key findings was around reasons for pupils not having scanned a QR code. The key responses are set out below:

-

Not enough time to scan.

-

No access to a mobile phone.

-

Unable to find a QR code.

-

Do not walk to school.

Staff Feedback

Whilst teachers were generally supportive of the scheme, key issues raised by staff included:

- Additional administrative burden of the scheme for staff on a morning.

- Difficulties with changes in staff contacts.

- Perceived limited impact on travel behaviours.

- Problems with the scheme running at same time as Journey to Jupiter and no clear communication that journeys could be recorded in similar way for both.

- Lack of clarity on how to implement the scheme.

Surveys

Introduction

A series of pupil and parent/carer surveys were undertaken to support the evaluation of the scheme. This section summarises findings from these surveys.

Pupil Survey

The pupil survey was sent to each school around the time of every school visit. An online survey link was sent to school contacts and head teachers, to be circulated around all class teachers. Class teachers were asked to undertake the hands-up style survey, by recording the number of pupils who usually travelled by each mode and inputting the results into the survey online.

- The first survey ran from 9th June to 30th June and obtained responses from 65 classes representing 1430 pupils.

- The second survey ran from 10th October to 31st October and obtained responses from 34 classes representing 676 pupils. Note that Coylton and Mauchline did not participate due to the aforementioned delay in launching the scheme, and no responses were received from New Cumnock or Whatriggs.

- The third survey ran from 24th November to 22nd December and obtained responses from 34 classes representing 786 pupils. Note that only the SAC/EAC schools were included in the final survey since the NAC trial finished shortly after the second school visits.

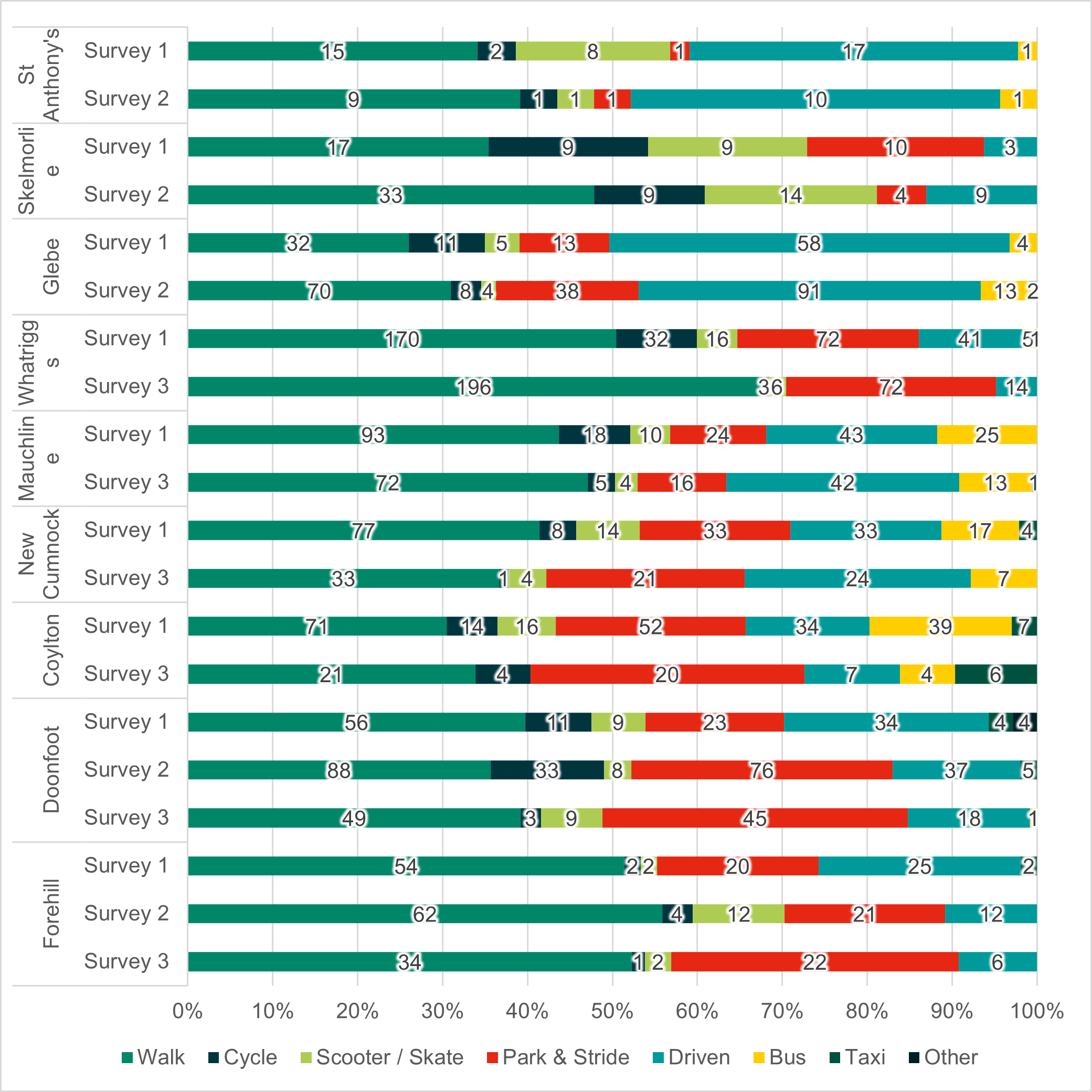

Figure 4 shows the travel to school mode share for each school for each survey. In the first survey, for most of the schools, active modes made up the majority of travel to school. However in Glebe, car was the most common mode, while in Coylton there was a greater share of park and stride, driving, bus, and taxi. This likely reflects the more rural nature and large geographical area of Coylton’s catchment, and the significant proportion of Glebe pupils who live outside the school’s catchment area.

In some of the schools, such as Doonfoot, Glebe, and St. Anthony’s there was a decrease in active mode share between the first and second survey. This is likely to reflect changes in weather due to seasonality. However some schools did show an increase in active mode share between the initial survey and subsequent surveys including Forehill, Whatriggs and Skelmorlie.

Only Forehill and Doonfoot had data for both survey two and survey three. In both, the active travel mode share decreased slightly between the second and third survey, likely due to a deterioration in the weather, although potentially also reflecting a drop-off in interest/engagement with the scheme.

Parent/Carer Survey

Introduction

Two parent/carer online surveys were undertaken per school; the first survey measured the baseline and was administered to all schools. The second and third surveys measured the post-implementation findings, with the second survey only applying to NAC schools (due to the shorter implementation period in NAC) and the third survey only applying to SAC/EAC schools.

The parent/carer survey link was sent to each school (via school contacts/headteachers) around the time of every school visit, to be circulated around all parents/carers and via social media where appropriate. For the post-implementation surveys, schools were also encouraged to promote the survey via QR code posters at the school gate/around the school (see Appendix D).

- The first survey ran from 9th June to 30th June and obtained responses from 448 parents/carers representing 614 pupils. No responses were received from Coylton.

- The second survey ran from 26th October to 17th November and obtained responses from 42 parents/carers representing 54 pupils. As noted, only the NAC schools were included in the second survey. No responses were received from St. Anthony's.

- The third survey ran from 24th November to 22nd December and obtained responses from 117 parents/carers representing 165 pupils. As noted, only the SAC/EAC schools were included in the third survey since the NAC trial finished shortly after the second school visits.

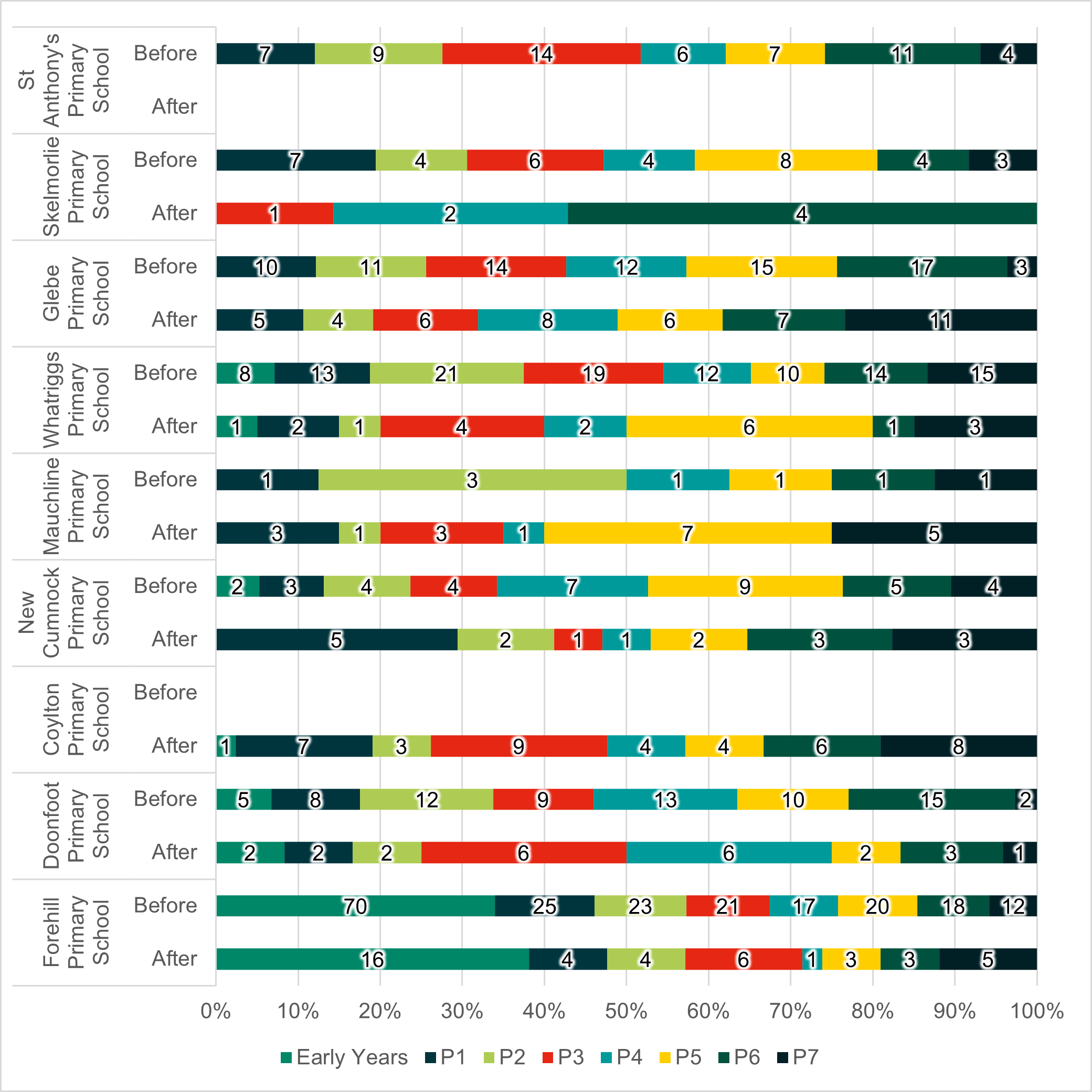

Figure 5 presents the number of pupils per year group represented in each of the parent/carer surveys. There was generally good representation of a range of year groups for each school in each survey.

Travel to School

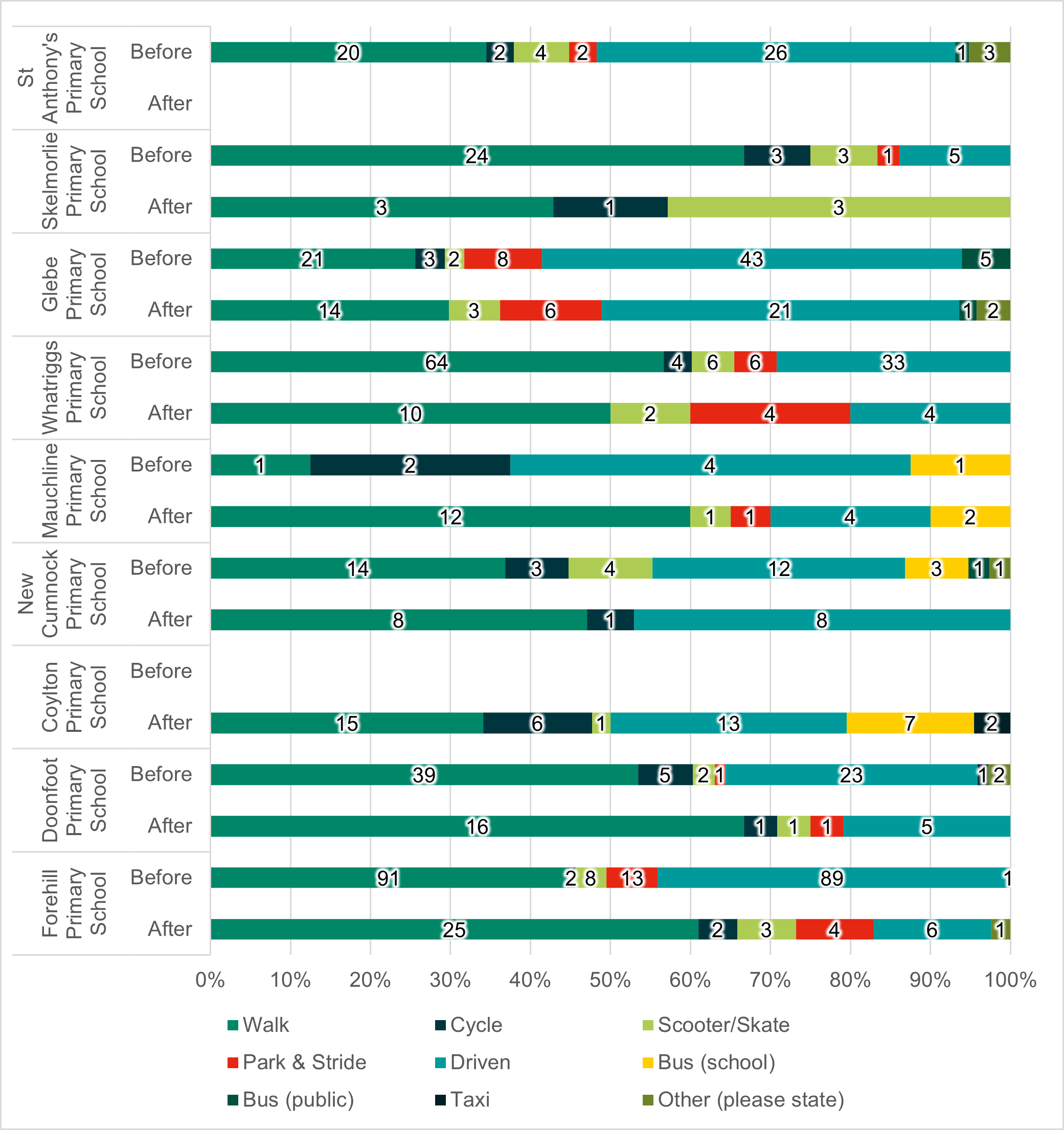

Figure 6 shows the travel to school mode share reported for each of the parent/carer surveys. Parents/carers were asked how their child normally travels to school. The baseline results reflect the findings of the pupil survey; that the majority of pupils travel actively to school, except at St Anthony’s and Glebe.

The impact of the scheme appears more positive based on the parent/carer survey than on the pupil survey. An increase in active travel share was observed in all schools except Whatriggs and New Cumnock, and although there was a slight decrease in active mode share in Whatriggs, the park and stride share increased and the share who were driven to school decreased.

Parents/carers were asked the main reason for their child’s travel to school mode choice. Response themes included:

- Distance from the school affects whether pupils can travel actively.

- Health and wellbeing benefits of active travel.

- Difficulties parking around the school encourages some to travel actively.

- Parents/carers dropping their children off at school, then travelling elsewhere (e.g. to work) means car is more convenient.

- Safety issues, such as a lack of suitable crossings, prevent active travel.

- Health issues make active travel difficult.

- Weather makes active travel less attractive.

- Pupils travelling alone encourages independence.

- Travelling actively saves money.

- Lack of mode choice, e.g. no access to a car means some have to walk or take public transport, or no public transport means some who live far from school have to drive.

- Risk of losing bus service means parents/carers want to ensure it’s used so it’s available in future to those who need it.

- Travelling actively to participate in the Trailblazers scheme.

- Enjoyment of active travel, particularly bike/scooter.

Parents/carers who said their child did not walk, cycle, scoot, or skate to school were asked if they could. In the baseline surveys, 54% of those who did not travel actively to school said they could. This varied between schools, and was highest in New Cumnock (82%) and lowest in Glebe (39%). There was not a significant difference in the findings for the subsequent surveys, although in Coylton (where there was no baseline data) only 23% who did not travel actively to school said they could.

For those who could travel actively, but did not, in the baseline survey the most common reasons were time constraints and the parent/carer travelling elsewhere directly from school.

For those who could not travel actively, in the baseline survey the most common reason was distance from the school. Other reasons given (i.e. those not included within the fixed responses) included the weather, safety issues, and health conditions and mobility issues.

Additional graphs with full results from the online parent/carer survey are presented in Appendix E.

Views on Road Safety and Active Travel

Parents/carers were asked for their views on the following statements, to assess perceptions and understanding of road safety and active travel:

- It is safe for my child to travel to school actively.

- My child is aware of road safety risks and knows how to keep themselves safe.

- There is too much traffic around the school.

- Parked cars around the school make crossing the road difficult.

Responses were recorded using a Likert-style scale as follows:

- Strongly Agree

- Agree

- Neither Agree nor Disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

- Don’t know

A detailed breakdown of the responses is presented in Appendix E.

In the baseline survey, parents’/carers’ views on whether it was safe for their children to travel to school actively were mixed. The majority of parents/carers in St Anthony’s, Skelmorlie, and Mauchline agreed, and in Forehill and Doonfoot more agreed than disagreed. However, in Glebe, Whatriggs and New Cumnock, more parents/carers disagreed than agreed. In most of the schools, the level of agreement remained similar between the surveys, however in Glebe, New Cumnock, Doonfoot, and Forehill there was an increase in perceived safety, while in Skelmorlie there was a decrease in perceived safety.

In the baseline survey, parents/carers generally agreed that their child was aware of road safety risks and knew how to keep themself safe. In the post-implementation surveys, agreement with this statement increased in Glebe, Mauchline, and Forehill, decreased in Skelmorlie and Doonfoot, and remained similar in the other schools.

In the baseline survey, parents/carers generally agreed that there is too much traffic around the school, except in Skelmorlie. In the post-implementation surveys, agreement with this statement decreased in Skelmorlie, Whatriggs, and Forehill, increased in Mauchline and Doonfoot, and remained similar in the other schools.

In the baseline survey, parents/carers generally agreed that parked cars around the school make crossing the road difficult, except in Skelmorlie. In the post-implementation surveys, agreement with this statement decreased in Glebe, Whatriggs, Mauchline, New Cumnock and Forehill, and increased in Skelmorlie and Doonfoot.

Overall there was some evidence that parents/carers felt travel to school was safer, pupils were more aware of road safety risks, traffic decreased, and parking reduced making it easier to cross the road. Considering the likely effect of seasonality and weather differences between the survey periods, these findings are promising.

Views on the Scheme

Parents/carers were generally aware that their child’s school was taking part in the scheme. Awareness was highest at Mauchline (100%) and lowest at Skelmorlie (57%).

Parents/carers were aware of the scheme through various channels. Overall 40% became aware via correspondence from the school, 35% saw the promotional material around the school (e.g. lamppost wraps on way to school / banners at the school gate) and 25% were made aware by their child.

Overall 27% of parents/carers said they or their child had scanned a Trailblazers QR code to see the daily message, question or challenge. This was highest in Skelmorlie (50%) and lowest in New Cumnock (10%).

Reasons for not having scanned a QR code included:

- Not present on route to school.

- Lack of awareness.

- Lack of interest.

- Time constraints.

- Didn’t have a device.

- Discouraging screen time.

- Travelling by other modes.

- Problems getting the code to scan.

- Not convenient to stop when walking/cycling.

- Safety concerns about being distracted.

Overall 36% of parents/carers said they thought the information provided had helped to improve their child’s road safety knowledge/awareness. This ranged from 75% in Mauchline, to 20% in New Cumnock.

Reasons for these responses included:

- Good way to engage pupils and talk about a serious subject in a fun way.

- Good branding and easy for children to understand.

- Did not scan code, so didn’t benefit.

- Pupils already aware of road safety issues

- Pupils didn’t absorb the information in the morning rush.

- Pupils had additional support needs.

- Didn’t address unsafe driving around the school – road safety rules only work if drivers follow them too.

Parents/carers were asked for their views on various statements, to assess the impact of the scheme.

Responses were recorded using a Likert-style scale as follows:

- Strongly Agree

- Agree

- Neither Agree nor Disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly Disagree

- Don’t know

Agreement (agree or strongly agree) with the statements was as follows:

- The Trailblazers scheme has encouraged my child to walk/cycle/scoot/skate to school (35%).

- The Trailblazers scheme has increased my child's understanding/awareness of road safety (38%).

- The Trailblazers scheme has made me feel more comfortable that my child can travel to school safely (29%).

- My child has enjoyed participating in the Trailblazers scheme (56%).

This shows some positive impact of the scheme, with the final statement in particular showing positive engagement with / enjoyment of the scheme. Enjoyment was highest at Skelmorlie and Glebe (both 75%).

67% of parents/carers agreed they would support a continuation/extension of the Trailblazers scheme. This was highest in Skelmorlie at 100% and lowest in Coylton at 48%.

Reasons for responses (from both those who were supportive and those who were not) included:

- The scheme has not addressed the traffic and parking issues at the schools.

- The scheme has helped conversation about road safety.

- The scheme has been good for children’s health.

- The scheme has encouraged others to leave their cars at home.

- Education is still required for both pupils and parents/carers on road safety.

- Would need more parent/carer engagement and a better explanation of the scheme.

- Impact on child’s road safety awareness is not clear.

- Pupils now often ask to walk part of the way to school.

- Pupils on bikes and scooters on the pavements on the way to school cause problems for those walking.

- Parents/carers feel bad if they are unable to walk their children to school.

- The scheme has exacerbated feelings of isolation for children who live far away from the school or outside the catchment area and therefore have more difficulty taking part.

- In some cases there has been pressure to park and stride instead of using the bus.

- The scheme has been fun, but improved crossings and better enforcement of existing restriction would make a more tangible difference.

- The scheme has improved pupil confidence.

Parents/carers were asked for any other feedback on the scheme. Comments included:

- Telling pupils they should travel actively to school can make those who are unable to do so feel bad.

- Some pupils have felt anxious on days where they had to be dropped off- perhaps the focus should be more on parents/carers, because pupils (particularly younger ones) are not always able to influence how they travel to school.

- The JRSOs leading the scheme has helped generate buy-in from the pupils, as it’s their peers encouraging them.

- Better road safety education is required for parents/carers.

- Better enforcement of parking restrictions is required.

- Roadworks around Doonfoot have had a negative impact on safe travel to school due to closures and construction traffic, potentially limiting any positive effects of the scheme.

- Better crossing facilities and/or more crossing patrols are required.

- Better access to secure bike sheds would be beneficial.

- Pupils do not all have phones, and the QR codes do not work on all phones. Is there a way this could be done without relying on technology?

- Removal of bus only access at Doonfoot has made it easier for people to drive, and has countered/limited any impact of Trailblazers.

- More information on the scheme would be useful.

- Some parents/carers have no choice but to drop off pupils on their way to work, and have nowhere safe to do so because the school car park is for staff only, restrictions around the school prevent safe drop off and not all parents/carers can afford breakfast clubs.

- Information leaflet provided wasn’t very clear. Pupils didn’t see the point in the QR codes and didn’t understand how to win the prizes.

- Pavement parking is an issue that needs to be addressed.

- Practical road safety lessons at school would be helpful.

- Lamppost wraps are on main road routes, but not on all walking routes.

- Could luminous stickers be provided for coats/bags to improve visibility of children walking?

A full breakdown of the quantitative responses to the parent/carer survey is presented in Appendix E.

Social Media

There was some promotion of the scheme via school websites and social media. New Cumnock Primary school promoted the evaluation surveys via their website, and St. Anthony’s promoted their whole school walk (where the whole school was taken out during school time to show pupils how to scan QR codes) on Twitter, which received good engagement.

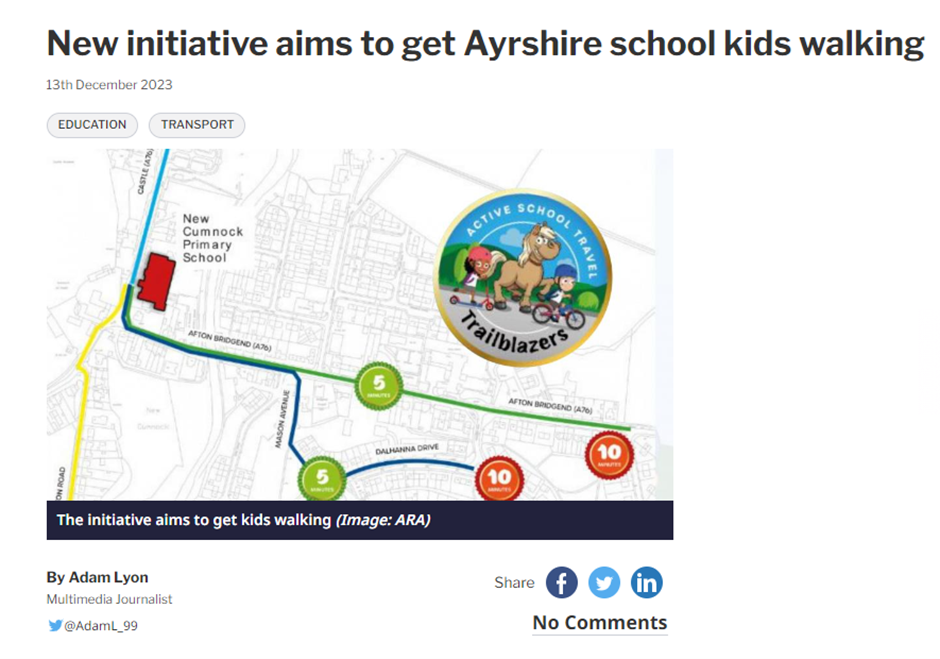

There was interest in the project from a number of traditional news outlets. The road safety operative from Ayrshire Roads Alliance was interviewed for a news bulletin that was featured on That’s TV on 14th December. There was also an article in the Cumnock Chronicle, Largs and Millport News, Irvine Times, and Ayrshire Today on 13th December.

A review of feedback associated with the press and social media posts has been undertaken but showed limited feedback.

Website and QR Code Usage

The Trailblazers website was launched and maintained by Ayrshire Roads Alliance, and had four key pages, set out below:

- Home: Presenting key information on the scheme and reasons to become a Trailblazer.

- Get Involved: Presenting additional information on the scheme and answering a number of FAQs.

- Maps: Presenting maps for each school with routes to school and sign locations.

- Questions: The daily question, fact or challenge, accessible via the QR codes.

Data from August to December showed that:

- 605 people had visited the “Home” page 748 times.

- 149 people had visited the “Get Involved” page 170 times.

- 148 people had visited the “Maps” page 280 times.

- 618 people had visited the “Questions” page 683 times.

Maps showing routes to school and locations of signs were provided for East and South Ayrshire schools, but were not available for North Ayrshire schools.

The findings are surprising because the premise of the scheme is that the question page is accessed daily. However, the data suggested that there were more return visits to the “Home” page than to the “Questions” page. Potential reasons for this finding are explored in the section below.

Lessons Learned

This section summarises key lessons learnt and has been informed by the findings from the school visits, surveys, and through discussions with road safety operatives.

- All schools starting simultaneously made the set up more challenging and launching in the new school year was not ideal because there was so much else going on at that time for the schools, and this contributed to delays in implementing the scheme at some schools.

- It was suggested that there could be benefits from trialling all the schools in one town to see what the effect would be.

- ‘Twilight’ briefing sessions with teachers were useful. These were held at the outset of the project to forewarn schools about the trial and the expectations on them, and also in between the second and third school visits to encourage participation amongst those schools where there had been a delay in launching the trial. In particular, the second session allowed schools to share ideas and experience from implementation. For example one school undertook whole school walks to show the pupils how to scan the QR codes, and allocated a certain number of prizes per class to make the distribution fairer and more manageable. In subsequent visits it was noted that other schools had adopted some of the ideas discussed in the briefing sessions, for example Coylton had undertaken a Santa walk.

- Some schools such as St Anthony’s and Doonfoot introduced a quiz element where pupils were tested on the QR code questions. This seemed an effective way of linking the QR codes with the prizes and reinforcing the road safety aspect of the scheme.

- As noted in the introduction, there were some differences in how the materials were used. In NAC it was not possible to use lamppost stickers due to local rules. However in EAC/SAC it was felt that the stickers provided more flexibility and were less prone to vandalism/removal than the lamppost wraps, which in EAC/SAC were treated as additional advertising, but not crucial to the scheme. The stickers could be used for example on both sides of the road to prevent pupils from having to cross the road to scan the QR code.

- The clash with the Journey to Jupiter scheme caused some issues with early implementation at some of the schools in EAC, and the schools reported that the administrative burden would be too high. However, once it was explained that the Journey to Jupiter record sheets could be used to inform the Trailblazers prizes, the schools were able to implement the Trailblazers scheme fully. Discussions with schools during the final visits suggested that the schemes were compatible and in practice there had not been significant issues with implementation of both schemes.

- There was flexibility in how the prizes and certificates were awarded, which allowed for inclusion of pupils who might not otherwise have been able to participate; for example pupils who get the bus to school. However some of the staff discussions noted that they were not clear when aspects of the scheme were supposed to be launched and how long the scheme was supposed to go on.

- One respondent to the parent/carer survey felt that the scheme focused on the journey to school, and did not prioritise active travel home in the evening. This was not understood to be an intentional distinction within the scheme, and highlights potential differences in how the scheme impacted behaviours, arising from the flexibility in how prizes were awarded at the individual schools.

- Changes in staff caused some difficulties with implementation in Coylton, however this was addressed through communication with the road safety operative, including an additional visit to the school.

- During the initial pupil focus groups, some pupils highlighted a risk that the scheme could have a negative impact on road safety if pupils were distracted by their phone when walking to school. This was not raised as a concern by pupils during the subsequent visits, however this could simply be due to a lack of awareness about the risk.

- Discussions with pupils highlighted some vandalism of the infrastructure, particularly at New Cumnock, but also at Glebe, Coylton, and Mauchline. In NAC, weekly checks were made, and any missing/damaged signs were repaired or replaced. In the EAC/SAC schools, due to the greater number of QR code stickers and the lower emphasis placed on the lamppost wraps, the schools were asked to monitor the signs for vandalism and report any issues.

- The QR code data showed that the Trailblazers homepage had been visited more/as many times as the question page. This was surprising because it would be expected that pupils would revisit the question page daily. Discussions with the IT team behind the website suggested that this could be due to issues with cookies; the tracker only works if the user accepts cookies, otherwise visits are not tracked. It is also possible that the QR codes on the lamppost wraps in SAC/EAC, and on the school gate banners may have caused confusion, because they led to the main website, not the daily questions/tasks. These could have been scanned by the general public passing-by, but discussions with pupils suggested some confusion about which QR codes to scan. However, the pupil focus groups suggested that although there was generally good engagement with the scheme, pupils were not always scanning the QR codes as part of their participation. Similarly, in the parent/carer surveys only 27% said they or their child had scanned a QR code, despite 56% saying their child had enjoyed participating in the scheme as a whole. Noting these findings, and the fact that participation in the scheme is not contingent on QR code use, overall this may suggest that the QR code aspect of the scheme was less effective than other aspects of the scheme, such as the record sheets and prizes.

- It is understood from discussion with the road safety operatives that other local authorities have already been in touch to replicate the scheme.

- Prior to scheme implementation, pupils highlighted potential security risks with the QR codes. During the scheme operation, there was a news report about criminals replacing genuine QR codes for parking payment at rail stations with their own codes and using this to defraud people (BBC News Article). Ayrshire Roads Alliance’s IT team were aware of these potential issues; however it was considered low risk in the case of Trailblazers since no personal information was collected. The Trailblazers website clearly states, “The website will never ask you for personal details or to enter any information.”

- Levels of engagement varied between schools. During the second school visits, engagement with the scheme was generally higher at the North Ayrshire schools, particularly St. Anthony’s and Skelmorlie, although there was also good early engagement from some of the EAC/SAC schools such as Forehill. It is difficult to attribute this difference to one particular reason, but the following factors could have contributed to this:

- The trial ran for a shorter time in the North Ayrshire schools (12 weeks compared to 18 weeks in the EAC/SAC schools).

- The North Ayrshire schools were selected based on their keenness to take part in the scheme.

- As previously noted, there was a delay in the implementation of the scheme, particularly the prize aspect, in some of the EAC/SAC schools. Engagement from many of these schools improved by the third school visits, with noticeable improvement at Doonfoot in particular.

- In schools where the feedback on the scheme was very positive, such as Forehill, this tended to coincide with high levels of involvement from both the pupils and the teachers. In Forehill the focus group was made up of the JRSOs, who had been responsible for the monitoring of the record sheets and administration of the prizes, and were clearly invested in the scheme. More generally, there seemed to be better engagement from the schools which actively requested to be involved in the scheme.

- Feedback from the parent/carer survey suggested that people who drove to school had more time to scan the QR codes as they arrived earlier. There was a perception that pupils who were driven to school but scanned the codes were being awarded prizes whereas children who walked but did not scan the codes did not receive any prizes.

Through the evaluation, a number of lessons learnt have also been identified, including:

- In line with the specification set out by the client group in the project tender brief, three rounds of surveys were undertaken, to establish a baseline and monitor findings. The surveys were kept consistent between rounds. Advantages to this approach are that it provides a snapshot of opinions at a point in time, and does not rely on respondents to remember and accurately report how their views or behaviours have changed over time. However, there were some disadvantages to this approach, including that the surveys were quite repetitive, which could have contributed to consultation fatigue; the response rates were lower for the “after” surveys which were crucial to understanding the impact of the scheme; and there was no guarantee of continuity of respondents, meaning that any differences in the results could be due to differences in the make-up of the respondents.

The specification for the evaluation was largely qualitative in nature, with findings based on results from pupil focus groups, teacher discussions, pupil surveys, and parent/carer surveys. In line with the request from the client group, the pupil focus groups tended to involve Junior Road Safety Officers (JRSOs) or other pupils with an interest in active travel or road safety. These pupils had a greater insight and first-hand experience of the scheme, but their views may not necessarily have represented the wider views of pupils across the school. While the surveys were promoted across the schools, they were not compulsory, so respondents were self-selecting. This means that views obtained from the surveys may not be representative of the wider school community.