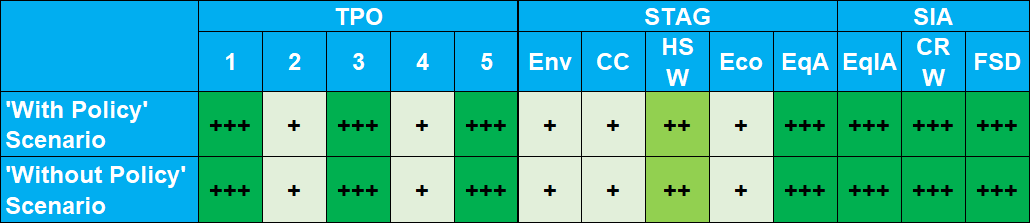

Preliminary Appraisal Summary Table - Active Communities

Preliminary Appraisal Summary

Option Description

Active Communities

This option would deliver networks of high quality active travel routes and placemaking improvements within key communities along the A96 Trunk Road corridor. Improving local places and active travel facilities within communities is not dependent on additional trunk road capacity on the A96 or the addition of bypasses. This option would seek to improve the local environment and economy of communities along the A96 corridor and thereby reduce the need to travel unsustainably.

Where bypasses are proposed in certain locations as a result of the A96 corridor review, resulting in reduction of through traffic within communities, then the active travel improvements within this option could be delivered as part of the ‘detrunking’ work. Creating ‘Active Communities’ within settlements along the A96 corridor, where road space is prioritised for the movement of people rather than motorised traffic, would ‘lock in’ the benefits of any proposed bypasses.

This option draws from the ‘20-minute neighbourhood’ concept (10 minutes there, 10 minutes back) and is built around an approximate radius of 800m from the centre of each settlement. Greater space for walking, wheeling and cycling within each settlement would be intended to better connect local centres with nearby residential areas, amenities and public transport nodes. The interventions would aim to create safer routes to school and encourage more inclusive environments for people walking, wheeling, cycling, and spending time in their local areas. Active Communities interventions would integrate with, and build upon, numerous town centre and travel masterplans throughout the A96 corridor, including but not limited to, the Nairn Community Town Centre Plan ( The Highland Council, Town Centre Action Plans for Tain, Nairn and Fort William – NAIRN Community Town Centre Plan, 2015, ) , Elgin City Centre Masterplan ( Moray Council, Elgin City Centre Masterplan, 2021 ) , Moray Town Centre Improvement Plans for Forres ( Moray Council, Forres Town Centre Improvement Plan, 2022 ) and Keith ( Moray Council, Keith Town Centre Improvement Plan, 2022, ) and the Integrated Travel Town (ITT) masterplans already produced for Huntly and Inverurie ( Aberdeenshire Council, Huntly and Inverurie Integrated Travel Town masterplans, 2018 ) .

Interventions would be determined by the needs of each key community along the A96 corridor but could include:

- more equitable balance between transport modes

- reallocation of road space to better provide for walking, wheeling and cycling

- improved surfacing and lighting of foot and cycle ways

- improved cycle parking

- removal and/or rationalisation of on-street parking

- measures to reduce traffic volumes and/or speeds

- improved road crossing points

- urban realm improvements

- links to the ‘Active Connections’ between settlements along the A96 corridor.

Relevance

Relevant to all active travel users in the corridor

Better active travel provision would encourage more people to engage in active travel, creating more inclusive and equal communities whilst also improving health outcomes by increasing levels of physical activity. There would be particular opportunities for people vulnerable to social exclusion such as disabled, young and older people, and those without access to a car. Providing fair access to cycling, including adaptive cycles and e-cycles, is aligned with the Cycling Framework for Active Travel ( Transport Scotland, Cycling Framework for Active Travel - A plan for everyday cycling, 2023, ) . Active Communities is also directly relevant to the Active Travel Framework ( Transport Scotland, Active Travel Framework, 2020 ) and the overriding 2030 vision for walking or cycling to be the most popular choice for shorter everyday journeys in Scotland’s communities.

Encouraging increases in active travel use is relevant in providing attractive and flexible alternatives to private vehicle use, especially for shorter distance trips within communities. If the option is successful in engendering a modal shift, this would help to reduce the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions in support of the Scottish Government’s target of reducing the number of kilometres travelled by car by 20% by 2030 ( Transport Scotland, Securing a green recovery on a path to net zero: climate change plan 2018–2032 - update, 2020, ) , contributing on the path towards net zero emissions.

This option also supports Scotland’s National Strategy for Economic Transformation ( Scottish Government, Scotland’s National Strategy for Economic Transformation, 2022 ) , which sets out the Scottish Government’s vision to creating a more successful country through a wellbeing economy, noting the requirement to thrive across the economic, social and environmental dimensions. The strategy is clear on the ambition to make Scotland fairer, wealthier and greener, and a shift towards active travel use within communities can assist in achieving these aims.

This option is relevant to key communities along the A96, although the specific measures undertaken in each would be dependent on community needs and aspirations.

Estimated Cost

£51m - £100m Capital

Determining the estimated cost of this option is dependent on a number of factors including the location, scale and complexity of providing active travel routes and placemaking improvements within communities. Further analysis and assessment would be required throughout the various stages of design development, a level of detail beyond that which is undertaken as part of a Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance (STAG) appraisal.

As a result, the STAG appraisal does not define the user types, width, surfacing and other aspects such as how active travel routes could be provided within communities. The different types of interventions outlined in Section 1.1 are wide ranging and this has a significant impact on the potential capital cost of delivering such facilities within communities.

Capital costs for the implementation of Active Communities would depend on local constraints and the scale and number of interventions proposed but would typically be anticipated to be in the range of £0.5m to £30m per community/location. The total estimated cost to introduce Active Communities across the A96 corridor is expected to fall within the range of £51m - £100m.

Dependent on the nature and location of interventions and facilities, the responsible authority and asset owner on completion is most likely to be the appropriate local authority, with Transport Scotland responsible for those located on the trunk road. It is anticipated that the asset owner would take on the responsibility for operation and maintenance of facilities, which would have ongoing costs associated with it, in addition to construction costs.

Position in Sustainable Hierarchies

Sustainable Investment Hierarchy / Sustainable Travel Hierarchy

Within the Sustainable Investment Hierarchy, this option sits within ‘reducing the need to travel unsustainably’, through delivering high quality active travel routes and placemaking improvements within settlements along the A96 corridor. This option would also sit across both the ‘walking and wheeling’ and ‘cycling’ tiers of the Sustainable Travel Hierarchy.

This option would also contribute to all 12 of the NTS2 outcomes, as follows:

- Provide fair access to services we need

- Be easy to use for all

- Be affordable for all

- Help deliver our net zero target

- Adapt to the effects of climate change

- Promote greener, cleaner choices

- Get people and goods to where they need to get to

- Be reliable, efficient and high quality

- Use beneficial innovation

- Be safe and secure for all

- Enable us to make healthy travel choices

- Help make our communities great places to live.

Summary Rationale

Summary of Appraisal

This option makes a positive contribution to all the A96 Corridor Review Transport Planning Objectives (TPOs), STAG criteria and Statutory Impact Assessment (SIA) criteria in both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios. Active Communities would aim to increase the mode share of walking, wheeling and cycling in settlements through provision of active travel infrastructure and placemaking improvements, which would have a major positive impact on TPOs for contributing to Scottish Government’s net zero targets (TPO1), enhancing communities as places to support health, wellbeing and the environment (TP03) and providing a transport system that is safe, reliable and resilient (TP05). Active Communities can also assist in improving accessibility to public transport (TPO2) and contributing to sustainable inclusive growth (TP04), with minor positive impacts anticipated.

The option would also have a major positive contribution for the STAG Equality and Accessibility criterion due to the benefits expected for all people groups within communities as a result of the enhanced provision of active travel infrastructure for access to key locations. A moderate positive contribution to the Health, Safety and Wellbeing criterion is also anticipated. Active Communities also scores positively against the SIA criteria, with major positive impacts in relation to Equality, Child Rights and Wellbeing and Fairer Scotland Duty.

Active Communities are considered to be feasible and deliverable in key communities along the A96, although costs of implementation could be high depending on the location and scale of the intervention. Detailed local engagement and design work would be required to identify the most appropriate locations and types of intervention. General public support is anticipated for active travel interventions that improve safety and provide traffic-free routes, though there may be some opposition from those who drive if road space is reallocated for active travel.

It is recommended that this option is taken forward to the Detailed Appraisal stage.

Details behind this summary are discussed in Section 3.

Context

Problems and Opportunities

This option could help to address the following problem and opportunity themes. Further detail on the identified problems and opportunities is provided in the published A96 Corridor Review Case for Change ( Jacobs AECOM, A96 Corridor Review Case for Change, 2022 ) .

Relevant Problem and Opportunity Themes Identified in the A96 Corridor Review Case for Change

Safety and Resilience : From the analysis of accident data, the rural sections of the A96 Trunk Road have overall Personal Injury Accidents (PIA) rates lower than or similar to the national average based on all trunk A-roads of the equivalent type. There are, however, selected urban sections of the A96 Trunk Road that show an accident rate higher than the national average, with specific locations in Forres and Keith. The rate of Killed or Seriously Injured (KSI) accidents is also significantly higher in these two towns than the national average, nearly five times the national average in Keith and just above three times the national average in Forres. A number of rural sections of the A96 Trunk Road also have a rate of KSIs higher than the national average these being between Hardmuir and Forres, between Fochabers and Keith, between Keith and East of Huntly and between Kintore and Craibstone.

Socio-Economic and Location of Services : Employment and other key services tend to be found in the three most populous and key economic locations within the study area: Aberdeen, Inverness and Elgin. Considering the travel distances between these three key economic centres and the other settlements in the transport appraisal study area, travelling by sustainable modes is relatively unattractive.

The key economic centres contain essential facilities such as major hospitals as well as a much greater density of education facilities. In addition, almost half of the total jobs in the transport appraisal study area are found within these three locations. Outside of these three areas, people making a trip to a workplace are more likely to travel over 10km, therefore limiting the potential for active travel for some commutes.

Travel Choice and Behaviour (Problem) : The number of homes without access to a private vehicle in the transport appraisal study area is consistently lower than the Scottish average. Aberdeenshire has a high level of access to a private vehicle, with approximately 90% of households in Aberdeenshire within the transport appraisal study area having access to at least one vehicle and over half have access to multiple vehicles. There is a greater availability of cars in the rural areas across the transport appraisal study area. This combined with the travel to work mode shares, indicates a reliance on private vehicles for travel. Travel to work data suggests older people are more reliant on cars, so with the aging population in the transport appraisal study area, this is likely to increase the use of cars further.

Health and Environment : Transport is a major contributor to CO 2 emissions along the A96 corridor, particularly in the Aberdeenshire and Highland Council areas. Transport contributes over 35% of the total emissions in both Aberdeenshire and Highland Council areas and between 25% and 30% in Aberdeen City and Moray. This is potentially an outcome of the high dependence on cars for travel, long travel distances and the levels of road-based freight movements.

The route of the A96 travels through the centre of towns along the corridor such as Elgin and Keith, which puts a relatively large proportion of the population in close proximity to potential noise pollution and pollutants from transport emissions that affect local air quality.

Sustainable Economic Growth : The transport appraisal study area has shown growth in tourism spend in recent years with the rise of whisky tourism and the Speyside Whisky Trail a major component of the economy in this sector. There are opportunities to change the way in which visitors travel to and from the region, and around it. Walking and cycling tourism is one such opportunity and has the potential to create further economic growth by attracting new visitors to the region.

Health and Environment Impacts of Travel: Reducing the use of car travel throughout the transport appraisal study area, particularly for short trips that could be made without motorised transport at all, would help reduce the transport contribution to CO 2 emissions, an important requirement of the Scottish Government’s net zero target. Fewer vehicle kilometres travelled would also improve the local air quality, with associated health benefits in communities along the A96.

Travel Choice and Behaviour (Opportunity) : Travel choices throughout the transport appraisal study area would be increased through better integration of modes and the provision of more demand-responsive options. Physical accessibility at rail stations could also be improved to reduce the reliance on cars. Active travel will continue to play a key role in the transition to sustainable and zero carbon travel by reducing the reliance on private vehicles. In smaller, more remote areas and towns there is the potential to increase active travel with connections by safe walking and cycling infrastructure.

Interdependencies

This option has potential overlap with other A96 Corridor Review options and would also complement other areas of Scottish Government activity.

Other A96 Corridor Review Options

- Active Connections

- Bus Priority Measures and Park and Ride

- Improved Public Transport Passenger Interchange Facilities

- Elgin Bypass

- Forres Bypass

- Inverurie Bypass

- Keith Bypass

- Targeted Road Safety Improvements.

Other areas of Scottish Government activity

- Active Travel Framework (2020) ( Transport Scotland, Active Travel Framework, 2020 )

- Climate Change Plan 2018-2032 Update (Scottish Government, Securing a Green Recovery on a Path to Net Zero: Climate Change Plan 2018–2032 – Update, 2020,)

- Cycling Framework for Active Travel - A plan for everyday cycling (2023) (Transport Scotland, Cycling Framework for Active Travel - A plan for everyday cycling, 2023,)

- National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) ( Scottish Government, National Planning Framework 4, 2023 )

- National Transport Strategy 2 (NTS2) ( Transport Scotland, National Transport Strategy: Protecting Our Climate and Improving Our Lives, 2020, )

- National Walking Strategy (2014) ( Scottish Government, Let's get Scotland Walking - The National Walking Strategy, 2014 )

- Strategic Transport Projects Review 2 ( Transport Scotland, Strategic Transport Projects Review 2, 2022 )

- The Place Principle ( Scottish Government, Place Principle: Introduction, 2019, )

- Town Centre Action Plan (2013) ( Scottish Government, Town Centre Action Plan: Scottish Government response, 2013, ) .

Appraisal

Appraisal Overview

This section provides an assessment of the option against:

- A96 Corridor Review Transport Planning Objectives

- STAG criteria

- Deliverability criteria

- Statutory Impact Assessment criteria.

The seven-point assessment scale has been used to indicate the impact of the option when considered under the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ Travel Behaviour scenarios (which are described in Appendix A of the Transport Appraisal Report).

Transport Planning Objectives

1. A sustainable strategic transport corridor that contributes to the Scottish Government’s net zero emissions target.

Modal shift of short distance trips from car to more sustainable modes of transport (including walking, wheeling and cycling) reduces levels of air pollution and greenhouse gases ( STPR2 Active Travel Statistics Summary: Environment Benefits of Active Travel.). Data presented in the A96 Corridor Review Case for Change ( Jacobs AECOM, A96 Corridor Review Case for Change, 2022 ) suggests that walking accounts for over 50% of journeys under 2km for the local authorities within the A96 corridor. Therefore, an opportunity exists to increase this by creating safe active travel infrastructure which enables greater participation. Research carried out in Waltham Forest showed that interventions to reallocate road space from general traffic resulted in 56% reduction in motor traffic on average within one mini-Holland scheme area ( Cairns et al., Traffic Impact of Highway Capacity Reductions – Assessment of Evidence, 1998/2002, ) . More recent research on low traffic neighbourhoods shows that reducing the amount of motor traffic locally leads to an increase in active travel without pushing traffic onto neighbouring streets ( Thomas & Aldred, Changes in motor traffic inside London’s LTNs and on boundary roads, 2023, ) . In Scotland, an evaluation of 30 active travel projects funded by Transport Scotland demonstrated an estimated average rise in active travel trips of 54% after initial delivery ( Sustrans, Analysis shows increase in active travel after project delivery, 2021 ) .

Evidence also suggests that the interventions put forward in this option would positively encourage people to switch to a more active mode of travel for everyday journeys. Research found that, a year after implementation of mini-Holland schemes, it was 24% more likely that respondents had used a bike in the past week and people living near to where schemes had been implemented had increased their past-week time spent walking and cycling by an extra 41 minutes; 32 of the extra 41 minutes were walking, and nine cycling ( Aldred et al., Impacts of an active travel intervention with a cycling focus in a suburban context: One-year findings from an evaluation of London’s in-progress mini-Hollands programme, 2019, ) .

This option is expected to have a major positive impact on this objective under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

2. An inclusive strategic transport corridor that improves the accessibility of public transport in rural areas for access to healthcare, employment and education.

This option would increase accessibility to public services by improving facilities for walking and cycling in the local network. Enhancing active travel provision within key communities would connect residential and employment areas to public transport nodes (for example rail stations and bus stops, as relevant to each key community) and increase travel choices.

This option would enhance inclusiveness by improving connections to local shops and facilities without use of private vehicles, and so promoting modes that are accessible to all. This would reduce transport poverty for disadvantaged and vulnerable users and improve mobility and inclusion. Local active travel interventions would also enable a greater number of people to access public transport nodes safer and more convenient. It would be anticipated that this option would bring about an increase in multi-modal journeys within, and between, key communities adjacent to the A96.

Road danger is the biggest single barrier to active travel use ( Cycling Scotland, Attitudes and Behaviours Towards Cycling in Scotland, 2019, ) , with children and older people particularly affected. Inaccessible cycle infrastructure is the single biggest difficulty faced by disabled cyclists in the UK ( Wheels for Wellbeing, A Guide to Inclusive Cycling, 2019, ) as well as a significant barrier to users of adapted cycles. Women are under-represented in cycling ( STPR2 Active Travel Statistics Summary: Gender. ) . Improved local infrastructure can help overcome barriers for members of these and other disadvantaged groups.

Whilst this option would bring benefits in terms of improving access to transport in rural areas, the focus of this option on key urban/semi-urban communities along the A96 corridor may limit the positive impact on more remote rural areas.

Overall, as this option does not directly impact public transport, it is expected to have a minor positive impact on this objective under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

3. A coherent strategic transport corridor that enhances communities as places, supporting health, wellbeing and the environment.

Active travel is beneficial to physical health and mental wellbeing. Keeping physically active can reduce the risk of heart and circulatory disease by as much as 35% and risk of early death by as much as 30%, and has also been shown to greatly reduce the chances of asthma, diabetes, cancer and high blood pressure ( Sustrans, Health benefits of cycling and walking, 2019, ) . Adults who cycle regularly can have the fitness levels of someone up to 10 years younger ( Sustrans, Health benefits of cycling and walking, 2019 ) . People living in walkable, mixed-use neighbourhoods have higher levels of social capital which positively supports wellbeing ( ARUP, Cities Alive – Towards a walking world, 2016, ) . Improved public realm allows for people to gather and socialise. Public Health Scotland ( Public Health Scotland, Evidence Behind Place Standard Tool and Place and Wellbeing Outcomes, 2022, ) have linked the quality of public spaces to people’s perceptions of attractiveness of an area, contributing towards their quality of life.

By creating more pleasant, accessible, safer communities along the A96 corridor, this option would help realise these outcomes, with particular benefits likely to be realised by some of those people often disadvantaged at present, including children and disabled people.

This option could directly improve access to local health and wellbeing infrastructure within key communities, as a result of improved active travel provision. It could indirectly improve access to health and wellbeing facilities in the wider A96 corridor area, for example Raigmore Hospital in Inverness, Dr Gray’s Hospital in Elgin and Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, through improved linkages to public transport services.

This option is expected to have a major positive impact on this objective under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

4. An integrated strategic transport system that contributes towards sustainable inclusive growth throughout the corridor and beyond.

Reallocating road space and prioritising active modes can have economic benefits and provide better spaces for people to live, work and shop in. Typical increases in footfall in retail areas of up to 20-30% result ( Dundee City Council, Walking & Cycling: the benefits for Dundee, 2021, ) . Well-designed active travel infrastructure can also facilitate branding initiatives by raising the profile of towns and cities among consumers and businesses ( Living Streets, The Pedestrian Pound, 2014 ) . Regeneration of the public realm can boost commercial trade, increase local retail sales, raise rental rates and property values and provide opportunity for cost-saving cycle freight ( Dundee City Council, Walking & Cycling: the benefits for Dundee, 2021 ) .

In Scotland, an evaluation of 30 active travel projects funded by Transport Scotland demonstrated an estimated average rise in active travel trips of 54% after initial delivery ( Sustrans, Analysis shows increase in active travel after project delivery, 2021 ) . As such, the active travel improvements within communities along the A96 could improve the sustainable access to labour markets by encouraging employees to travel by active modes wherever possible and particularly for shorter journeys.

This option is expected to have a minor positive impact on this objective under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ Scenarios.

5. A reliable and resilient strategic transport system that is safe for users.

Improved pedestrian and cycling infrastructure together with other interventions such as speed reduction can significantly reduce road casualties. In 2018, 86% of cycling casualties and 95% of pedestrian casualties in Scotland occurred on built-up roads, with a speed limit of 40mph or less (Definition of a built up road is one with a speed limit of 40mph or less as per the DFT classification.). Accident survival rates are between about three ( Jones & Brunt, Twenty miles per hour speed limits: a sustainable solution to public health problems in Wales, 2017, cited at: ) and five ( Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, Road Safety Factsheet, 2017 ) times higher when a pedestrian is hit by a car driving at 20mph, compared to 30mph. The introduction of a Low Traffic Neighbourhood (LTN) in a London suburb led to a three-fold decline in the number of injuries in the area and estimated that walking, cycling and driving all became approximately three to four times safer per trip ( Laverty et al., The Impact of Introducing Low Traffic Neighbourhoods on Road Traffic Injuries, 2020, ) .

Public realm improvements such as the provision of street lighting can prevent road traffic collisions and increase pedestrian activity through reduction in the fear of crime ( Public Health England, Spatial Planning for Health – An evidence resource for planning and designing healthier places, 2017 ) . More people walking, wheeling and cycling in and around key communities would increase natural surveillance and so improve personal security. Findings from Waltham Forest, London, where an LTN has been implemented, shows that street crime reduced by 18% in the three years following implementation ( University of Westminster, The Impact of Introducing a Low Traffic Neighbourhood on Street Crime, in Waltham Forest, London, Aldred & Goodman, 2021, ) .

This option could also improve the resilience and reliability of the transport network through modal shift from car to active travel journeys, resulting in reductions in road congestion on urban sections of the corridor such as Elgin.

This option is expected to have a major positive impact on this objective under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

STAG Criteria

1. Environment

This option may result in positive impacts on communities and deliver health and wellbeing benefits (e.g. improved physical heath), as the option seeks to promote and facilitate a modal shift to sustainable and active travel with a focus on improved safety, connectivity and accessibility for all users. The proposal aims to reduce private car use which would have potential positive impacts in terms of reducing noise, air pollutants and greenhouse gases. This would help improve the local environment within communities through which the A96 currently passes where this option is implemented. Creating additional space for active travel would be of benefit to communities, by reducing severance caused by the trunk road network, allowing areas of the settlement to reconnect, and increasing the sense of placemaking. This would be in accordance with TPOs 1 and 3. This would also allow greater connectivity to local services within the community.

However, there is the potential for minor to moderate negative environmental impacts during construction and operation, on natural resources, the water environment, biodiversity, landscape and visual amenity, agriculture and soils, and cultural heritage for example, depending on how these active travel routes and placemaking improvements are constructed and their precise location. Such impacts could either be direct (such as demolition/land loss/habitat loss) or indirect (such as impacts on setting or views).

Further environmental assessment would be undertaken if such options are progressed through the design and development process, in order to identify potentially significant location-specific environmental effects and mitigation where appropriate. Design and construction environmental management plans would also be developed to consider how to protect and enhance landscape, drainage, amenity, biodiversity, and cultural heritage. Appropriate environmental mitigation and enhancement measures would also be embedded as the design and development process progresses.

Overall, this option is expected to have a minor positive impact on addressing this criterion under both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios, although this would be subject to the specific effects of the actual interventions chosen.

2. Climate Change

In the short term, greenhouse gas emissions would be generated due to construction activities undertaken to deliver active travel routes and placemaking improvements, including indirect emissions from the manufacture and transportation of materials and emissions from the fuel combusted by construction plant and vehicles.

However, in the longer term, this option would help facilitate a modal shift from car to active modes for short journeys in key communities along the A96. A reduction in car kilometres travelled would thus lead to a modest reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

It is estimated that if an average person were to switch one trip per day from car driving to cycling for 200 days per year, they would reduce their carbon footprint by approximately 0.5 tonnes over one year, representing a significant share of average per capita CO 2 emissions ( Brand, C., “Active Travel’s Contribution to Climate Change Mitigation: Research Summary and Outlook”, Active Travel Studies 1(1). 2021, doi: ) , which equates to approximately 9% of per capita CO 2 emissions (based on 2019 estimates of emissions that place CO 2 per capita emissions for Scotland at approximately 5.7 tonnes ( HM Government, UK local authority and regional carbon dioxide emissions national statistics: 2005 to 2019, 2021 ) ).

The option has the potential to be vulnerable to the effects of climate change impacting the A96 Trunk Road, e.g. material deterioration due to high temperatures leading to deterioration of surface such as softening, deformation and cracking, surface water flooding and damage to surfaces from periods of heavy rainfall. However, new infrastructure would be designed in such a way to minimise the potential effects of climate change, to reduce the vulnerability at that location.

This option is expected to have a minor positive impact on this criterion under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

3. Health, Safety and Wellbeing

Improved pedestrian and cycling infrastructure together with other interventions such as speed reduction can significantly reduce road casualties. In 2018, 86% of cycling casualties and 95% of pedestrian casualties in Scotland occurred on built-up roads, with a speed limit of 40mph or less (Definition of a built up road is one with a speed limit of 40mph or less as per the DFT classification.). Accident survival rates are between about three ( Jones & Brunt, Twenty miles per hour speed limits: a sustainable solution to public health problems in Wales, 2017, cited at: ) and five ( Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, Road Safety Factsheet, 2017, ) times higher when a pedestrian is hit by a car driving at 20mph, compared to 30mph. The introduction of a Low Traffic Neighbourhood (LTN) in a London suburb led to a three-fold decline in the number of injuries in the area and estimated that walking, cycling and driving all became approximately three to four times safer per trip ( Laverty et al., The Impact of Introducing Low Traffic Neighbourhoods on Road Traffic Injuries, 2020, ) .

More people walking, wheeling and cycling in and around key communities along the A96 corridor would increase natural surveillance and so improve personal security. Public realm improvements such as the provision of street lighting can prevent road traffic collisions and increase pedestrian activity through reduction in the fear of crime (Public Health England, Spatial Planning for Health – An evidence resource for planning and designing healthier places, 2017,). Findings from Waltham Forest, London, where an LTN has been implemented, shows that street crime reduced by 18% in the three years following implementation ( University of Westminster, The Impact of Introducing a Low Traffic Neighbourhood on Street Crime, in Waltham Forest, London, Aldred & Goodman, 2021, ) .

Walking, wheeling and cycling locally allows more people to feel connected with their local community and would improve public health. Improved public realm allows for people to gather and socialise. Public Health Scotland has linked the quality of public spaces to people’s perceptions of attractiveness of an area, contributing towards their quality of life.

This option could directly improve access to local health and wellbeing infrastructure within key communities, as a result of improved active travel provision. It could indirectly improve access to health and wellbeing facilities in the wider A96 corridor area, for example Raigmore Hospital in Inverness, Dr Gray’s Hospital in Elgin and Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, through improved linkages to public transport services.

Some negative impacts on visual amenity where new infrastructure is constructed could be anticipated. Further assessment will be undertaken to identify any impacts as part of the design development process.

Overall, this option is expected to have a moderate positive impact on this criterion under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

4. Economy

The A96 plays an important strategic role in the regional economy of the north-east of Scotland, connecting people to employment and education opportunities as well as providing businesses with access to the labour market.

This option would also result in wider economic impacts at a local level for both transport users and non-users, with the potential to result in positive changes to economic welfare. There is published evidence of benefits of improvements to public realm, walking and cycling to support to local and regional economies.

Well-planned regeneration of the public realm and accompanying enabling of active travel, using measures of the types proposed in this option, can typically boost local retail trade by up to 20-30% ( Living Streets, The Pedestrian Pound – The business case for better streets and places, 2018, ) .

Residential property values rise 1% if motor vehicle traffic is reduced by 50% ( Rajé & Saffrey, ‘The Value of Cycling’, 2016 ) .

Cycle parking can deliver five times the retail spend per square metre than the same area of car parking ( Rajé & Saffrey, ‘The Value of Cycling’, 2016 ) . Over a month, people who walk to local high streets spend up to 40% more than people who drive to the high street ( Transport for London, Walking & cycling: the economic benefits, ) .

An economic assessment to calculate the Transport Economic Efficiency (TEE) of this option has not been undertaken at this stage of appraisal as the route and standard of this option are currently unknown. No significant impact on TEE is anticipated.

This option is expected to have a minor positive impact on this criterion under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios due to the potential benefit to local businesses improvement to the public realm and a reduction in vehicles could bring.

5. Equality and Accessibility

Public realm improvements which support walking and wheeling have a role to play in increasing inclusion and reducing inequality. Between the local authority areas of Aberdeenshire, Moray and Highland, around 15% did not have access to a car in 2019 ( Scottish Government, Scottish Household Survey 2019 – Supplementary Analysis, 2020 ) .

This option would improve comparative access and transport inclusivity for commonly disadvantaged groups within key communities along the A96 corridor.

There are many social and community benefits associated with improving conditions for local active travel particularly to young people, older people and people with disabilities, all of whom are more likely to be restricted from accessing services and facilities by traffic dominated environments and other local barriers.

This option would improve active travel network coverage within the Active Communities. Whilst this option would improve active travel access to public transport routes and facilities, it is unlikely to impact on public transport network coverage.

This option would provide low cost travel options (walking, wheeling, cycling) within the Active Communities, but would not impact on the affordability of public transport.

Reference should also be made to the SIAs in section 3.5.

Overall, this option is expected to have a major positive impact on this criterion under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios as a result of the improvements to comparative access for commonly disadvantaged groups, social benefits created, and the increase in active travel network coverage to access key local destinations.

Deliverability

1. Feasibility

Dependent on the nature and location of interventions and facilities, the responsible overseeing authority and asset owner on completion could be Transport Scotland or the local authority. This is likely to be a function of the location(s) and types of interventions.

Although responsibility for construction, operation and maintenance is likely to be divided between Transport Scotland and local authorities, initial assessment for this option may be led by Transport Scotland, with input from local authorities and Regional Transport Partnerships.

Active Communities are readily feasible and would comprise more extensive roll-out of interventions for which there is already significant experience of implementation in Scotland.

A detailed assessment would be required to fully establish the details of the most appropriate routes and infrastructure for the development of Active Communities. Depending on the location of any new infrastructure or routes, local authority support may be required.

The engineering constraints would vary significantly from location to location along the A96 corridor within communities. This would include various existing residential and business properties, roads, rivers and railways that may intersect the locations. Any location would also have to consider geotechnical constraints, potentially poor ground conditions and various other environmental and planning/land use constraints which have been discussed in previous sections.

In some instances, infrastructure improvements may require reallocation of road space away from other modes. Where this is the case, design development would require balancing the sometimes competing aspirations for improved active travel routes with other sustainable transport modes e.g. public transport.

It is anticipated that the asset owner would take on the operation and maintenance of facilities post-construction.

Although there are some challenges as outlined above, the work undertaken to date indicates that this option is feasible.

2. Affordability

Delivery of this option would likely be phased over a number of years and would require further assessment to determine the most appropriate approach at each location. The cost in different locations would vary depending on the type and scale of active travel infrastructure introduced and locational constraints that may impact the complexity of construction. Therefore a more detailed review of each community would be required to determine the likely cost impact. Costs would be also dependent on a number of other factors, such as the requirement for earthworks and structures, localised ground conditions, the purchase of land and various other engineering and environmental constraints.

In addition to construction costs, and dependent on the location and nature of the active travel intervention, it is likely that Transport Scotland would be the asset owner for any infrastructure adjacent to the trunk road and the local authority for routes and infrastructure remote from the trunk road. It is anticipated that the asset owner would take on the operation and maintenance of facilities, which would have ongoing costs requiring revenue funding.

3. Public Acceptability

Data from a survey conducted in 2020 shows that the public are in favour of measures to encourage walking and cycling with six and a half people supporting changes to their local streets for every one person against ( #BikeIsBest, Press Release, July 2020, ) . In addition, from surveys in 12 UK cities, 55% of residents think too many people drive in their neighbourhood, 68% support building more cycling tracks even when this would mean less room for other road traffic, and 58% of residents would like to see more government spending on cycling ( Sustrans, Bike Life, ) .

However, whilst Active Communities interventions are typically popular post-implementation, some pre- and post-implementation challenges are expected from people who feel they would be adversely affected, in particular those that drive through affected areas or are directly impacted by construction works.

Public consultation undertaken as part of this review indicated general support for the active communities. There are concerns expressed regarding safety, lack of travel infrastructure, poor active travel links and few provisions for active travel. A total of 43% of those who responded were 'dissatisfied' or 'very dissatisfied' with the availability of safe walking and wheeling infrastructure. Similarly, approximately half of respondents were either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the ability to cycle safely. Active Communities would aim to provide safer routes safer for active travel modes. Provision of safer facilities was the number one reason that respondents suggested would get them to use active modes more, with 33% saying they would walk and wheel more with safer facilities in place, and 40% suggesting they would cycle more. This suggests that there would be general support for the Active Communities interventions.

Strategic Impact Assessment Criteria

1. Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA)

An SEA has been prepared and has helped inform the Environment criterion of the STAG appraisal. There is also considerable overlap between the SEA and the Climate Change criterion. The SEA utilises a set of SEA objectives that covers a wide range of environmental topics including Climatic Factors, Air Quality, Noise, Population and Human Health, Material Assets, Water Environment, Biodiversity, Geology and Soils, Cultural Heritage, Landscape and Visual Amenity. The full SEA, including scoring and narrative for each of the Preliminary Appraisal interventions and Detailed Appraisal packages is presented in the SEA Draft Environmental Report ( Jacobs AECOM, Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Draft Environmental Report - A96 Corridor Review, 2024 ) .

2. Equalities Impact Assessment (EqIA)

This option provides the opportunity for safer and affordable access to services for residents of key communities along the A96. This includes access to employment, education, health facilities and other transport services, including other active travel routes, which are important to many groups with protected characteristics. Through the reallocation of road space and improved surfaces and crossing points, the infrastructure installed could be designed to incorporate adapted cycles and, as such, address mobility issues experienced by commonly disadvantaged groups, such as women, disabled people and older people. Improved safety measures would also reduce road and personal safety concerns for active travel users, including children.

An uptake in active travel may additionally improve physical health and mental wellbeing outcomes and is also likely to lead to air quality improvements if the uptake is matched by a reduction in private vehicle use and traffic congestion. Improved health outcomes as a result of better air quality are of particular benefit to those who are more vulnerable to air pollution, including children, older people and disabled people.

However, the extent to which groups with protected characteristics would benefit from this option would depend on the extent to which all listed interventions can be adopted, as it is noted that this would depend on local circumstances within each key community. In addition, the extent of benefit would depend on the location and routeing of active travel networks and facilities, their proximity to local services and the ability for people to access the network. The effects of reallocation on road space on other road users could also have potential adverse effects on certain groups, such as disabled people who rely on parking spaces close to essential services.

Overall, this option is expected to have a major positive impact on addressing this criterion under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

3. Children’s Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessment (CRWIA)

This option is likely to lead to significant improvements for children due to:

- a reduction in the perceived danger of road accidents and casualties

- improved air quality if the uptake in active travel is accompanied by a decrease in private vehicle use and traffic congestion

- better and less costly access to education and other services

- the consequential effects of improved access to services for the whole community (such as parent and carer access to employment).

In addition, the habit-forming effect of embedding active travel at a younger age has the potential to have longer term benefits, in terms of moving to a more active population.

However, the extent to which this option would improve outcomes for children would depend on the extent that the interventions listed are adopted (especially in regard to the reallocation of road space and other safety measures), the location of the interventions, and proximity to local services.

This option is expected to have a major positive impact on this criterion under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

4. Fairer Scotland Duty Assessment (FSDA)

Beneficiaries of this option are likely to include more deprived areas within key communities, as this option would have consequential positive effects on improving access to services. As well as benefitting these ‘communities of place’, this option is likely to additionally improve access to services for ‘communities of interest’, including those with lower access to private vehicle use (such as women, young people and low-income households) and others who may benefit from less costly travel options. However, the extent to which this option would reduce inequalities of outcome would depend on the extent that the interventions listed are adopted, the location of the interventions, proximity to local services and the ability for those from deprived and disadvantaged communities to access the active travel network.

This option is expected to have a major positive impact on this criterion under both the ’With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.