Assessment of Impacts

Introduction

This chapter provides a high-level assessment of the potential impacts of Full Dualling and the packages of transport intervention options that are being considered as part of the A96 Corridor Review on socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

The assessment is based on the rating criteria set out in Section 5.3 and takes into account wider appraisal work and baseline evidence for socio-economic disadvantage.

For the purposes of the A96 Corridor Review, the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios developed as part of the scenario planning undertaken for STPR2, are used in the Detailed Appraisal of Full Dualling and each package. These demand scenarios were developed to consider the risk associated with future uncertainties. The following two scenarios with their inherent variants of transport behaviour were considered:

- 'With Policy Scenario' - captures policy ambitions including 20% reduction (from 2019 levels) in car kilometres travelled by 2030, and assumptions to significantly reduce levels of commuting/business journeys to reflect post COVID-19 working behaviours, leading to low levels of motorised traffic demand and emissions.

- 'Without Policy Scenario' - no policy ambitions are captured, and less significant reductions to levels of commuting/business journeys, leading to higher levels of motorised traffic demand and emissions.

Transport Intervention Packages

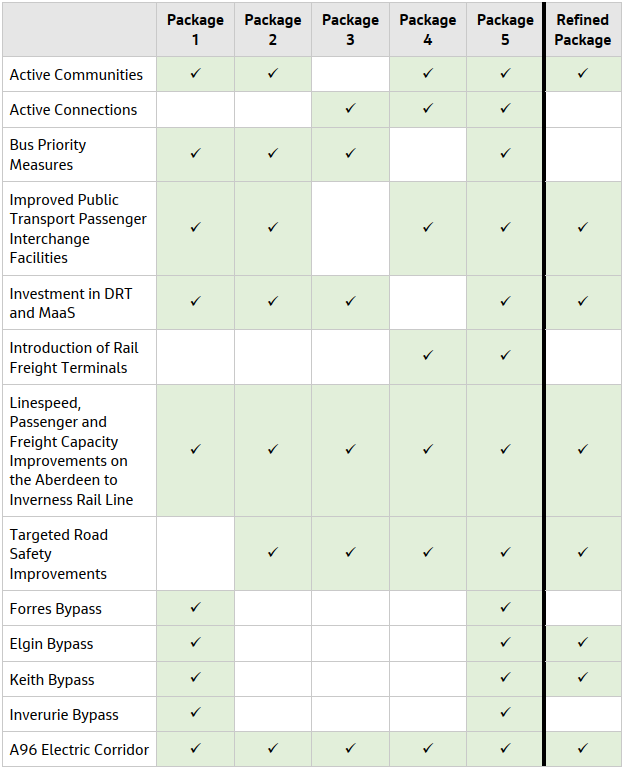

Full package descriptions and detailed appraisal summaries are included within the ‘Strategic Business Case – Transport Appraisal Report’ published alongside this FSDA. However, Table 6-1 provides a summary of the transport interventions included within each package. It should be noted that the A96 Dualling Inverness to Nairn (including Nairn Bypass) scheme does not form part of the A96 Corridor Review as it has successfully progressed through a Public Local Inquiry and has Ministerial consent. Interventions within Nairn itself, similar to those proposed within the other bypassed towns, however, have been included within the packages for appraisal purposes.

Table 6‑1: Interventions Within Each Detailed Appraisal Package

A96 Full Dualling – Potential Impacts

Figure 6‑1: A96 Full Dualling Hardmuir to Craibstone Extent

There is generally a heavier reliance on the use of the private car along the A96 corridor compared with the rest of the country. This is primarily due to the rural nature of the region, where there is greater dependency on the private car to access employment, education, healthcare and for social purposes. In the absence of viable alternatives to travel, some low-income households may have no alternative to car ownership despite financial constraints. However, there could be benefits through an improvement in journey times and reliability of journey times for these drivers, providing more economical and efficient journeys.

There are also opportunities for safety improvements to benefit socio-economically disadvantaged groups as evidence shows that people from deprived areas are more likely to be injured or killed as road users. Therefore, improved safety of the trunk road network through overtaking opportunities and reduced traffic flows in bypassed towns could benefit those living in deprived areas. However, it is acknowledged that wider factors affect road casualty rates and that more detailed assessment work is required to understand the safety benefits associated with individual schemes and how this might impact on people from deprived areas.

The construction works associated with full dualling could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Overall, full dualling is expected to have a minor positive impact under both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios for socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

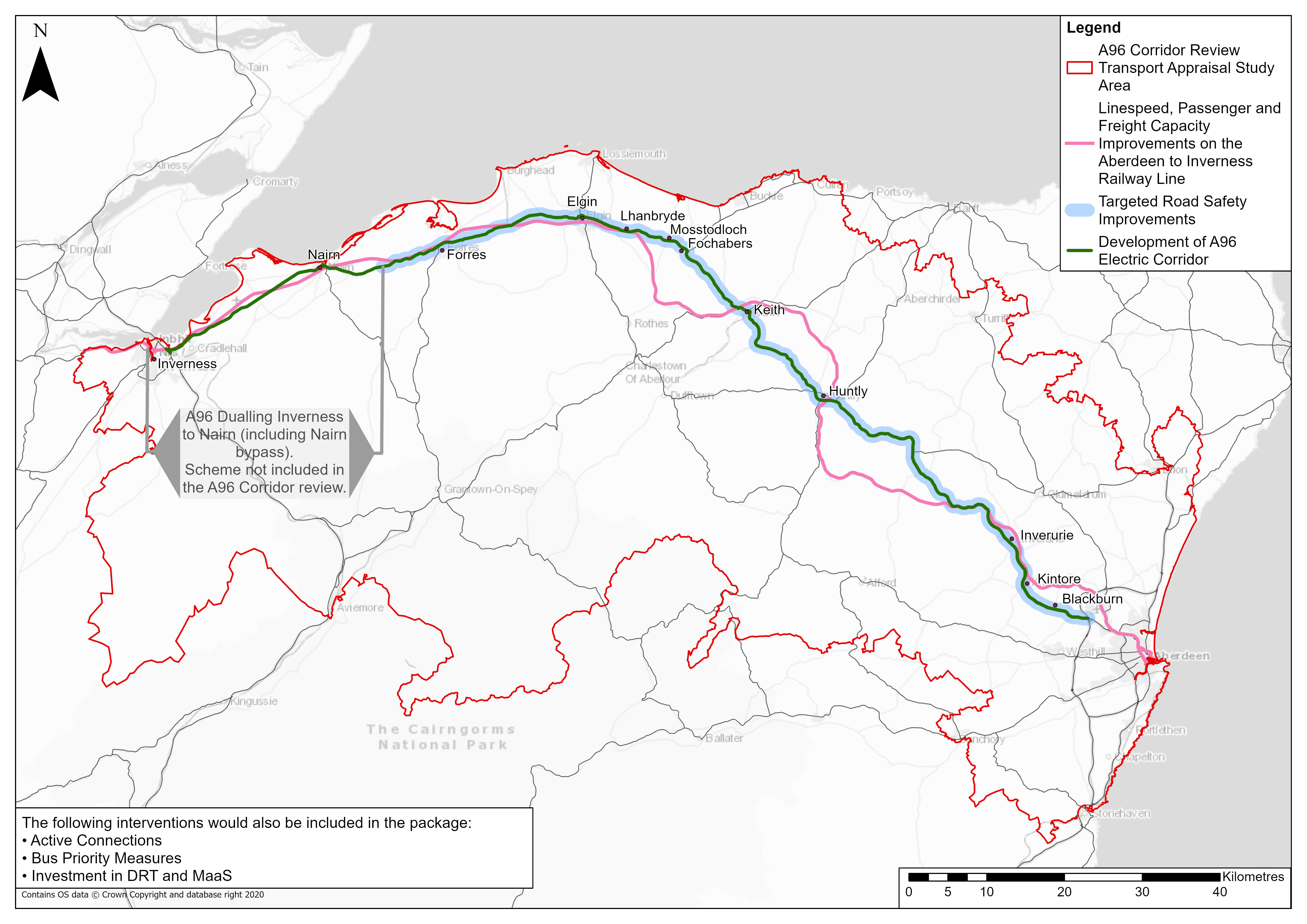

Package 1 – Potential Impacts

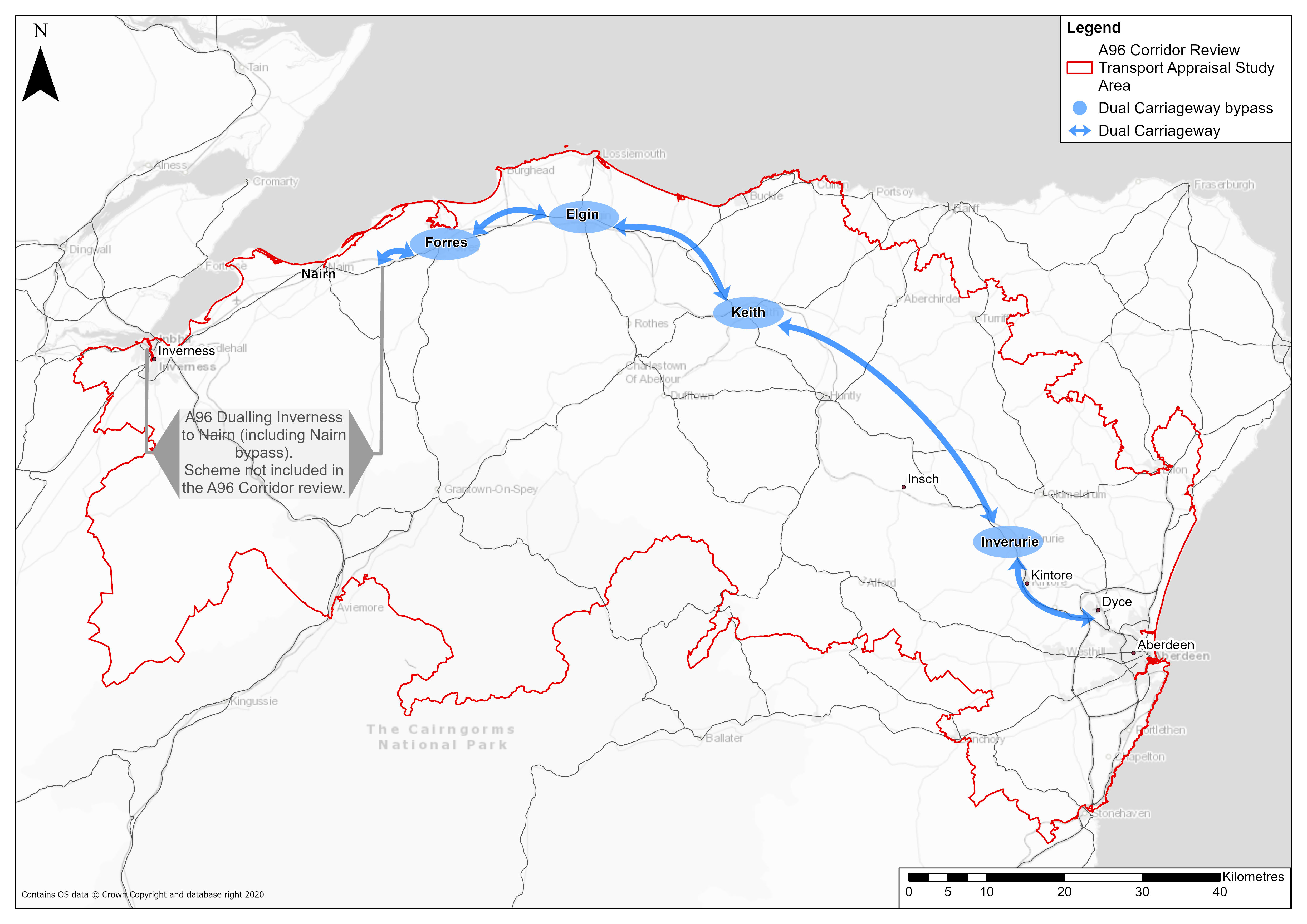

This package is focused on primarily delivering transport network improvements to key towns along the A96 corridor, namely Nairn, Forres, Elgin, Keith and Inverurie, by providing enhancements which would aim to encourage a shift to sustainable modes, increasing opportunities for residents and businesses and improving road safety.

The location of the settlements concerned in relation to the wider A96 Corridor Review transport appraisal study area is illustrated in Figure 6.2 . Whilst this package is primarily targeted at the aforementioned settlements, it also includes corridor-wide interventions which are anticipated to result in benefits to other areas within the corridor.

Figure 6‑2: Package 1 Extent

Modelling undertaken using Jacob’s National Public Transport Accessibility Tool (NaPTAT) anticipates that this package would improve access to essential services for socio-economically disadvantaged groups across the region, including employment and education sites located in major cities.

NaPTAT modelling observed the largest journey time accessibility benefits to key destinations and essential services in Aberdeenshire. These benefits would be linked to the rail interventions within the package and result in reduced public transport journey times between settlements along the rail line, particularly to Inverness and Aberdeen. The package would reduce the journey time to the nearest higher education site for 300 young people aged 16-24 who reside in areas where the gross household income is within the 20% lowest in the study area. Of these, 150 young people would be able to access their nearest higher education site within approximately 60 minutes and the remaining 150 young people able to access their nearest higher education site within approximately within 100 minutes. The increased accessibility of higher education along the A96 would largely be found in rural settlements including Kemnay and Alford (located to the south-west of Inverurie).

Further journey time accessibility benefits in Aberdeenshire would be observed in access to employment opportunities found in Aberdeen City for residents in geographically deprived areas (20% most deprived in the country). The package would enable, on average, an additional 3,100 existing jobs located in Aberdeen City to be reached within 60 minutes using public transport from geographically deprived areas in Aberdeenshire.

Traffic modelling forecasts predict that traffic would divert away from Forres, Elgin, Keith and Inverurie following the introduction of Package 1 in both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios. This is expected to create benefits for socio-economically disadvantaged groups by improving the active travel environment for those who are unable to afford a car. Including active travel interventions in conjunction with bypasses could aid the removal of barriers in communities through an improved sense of road safety and security for those walking, wheeling and cycling, and the public transport interventions included within this package could encourage modal shift to more sustainable modes. There is also the potential for a reduction in inequalities of health in disadvantaged and deprived communities through improved air quality at a local level.

There is generally a heavier reliance on the use of the private car along the A96 corridor compared with the rest of the country. This is primarily due to the rural nature of the region, where there is greater dependency on the private car to access employment, education, healthcare and for social purposes. In the absence of viable alternatives to travel, those on low incomes may have no alternative to car ownership despite financial constraints. Reductions in journey times and improvement in journey time reliability for drivers, could provide more economical and efficient journeys for these groups.

The provision of bypasses could reduce the number and severity of road traffic accidents on the sections of the existing A96 Trunk Road which route through towns. This could benefit socio-economically disadvantaged groups, as evidence shows that people from deprived areas are more likely to be killed or injured as road users. The construction works associated with bypasses could also result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups. However, it is acknowledged that wider factors affect road casualty rates and that more detailed assessment work is required to understand the safety benefits associated with individual schemes and how this might impact on people from deprived areas.

The extent to which positive effects would be realised depends on the alignment of bypasses and the level to which all other listed interventions are adopted, as it is noted that this would depend on local circumstances within each key community. This in turn would have an impact on the level of reduction of through traffic within disadvantaged and deprived communities.

The construction works associated with the interventions in this package could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Overall, this package is expected to have a minor positive impact under both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios on addressing this criterion.

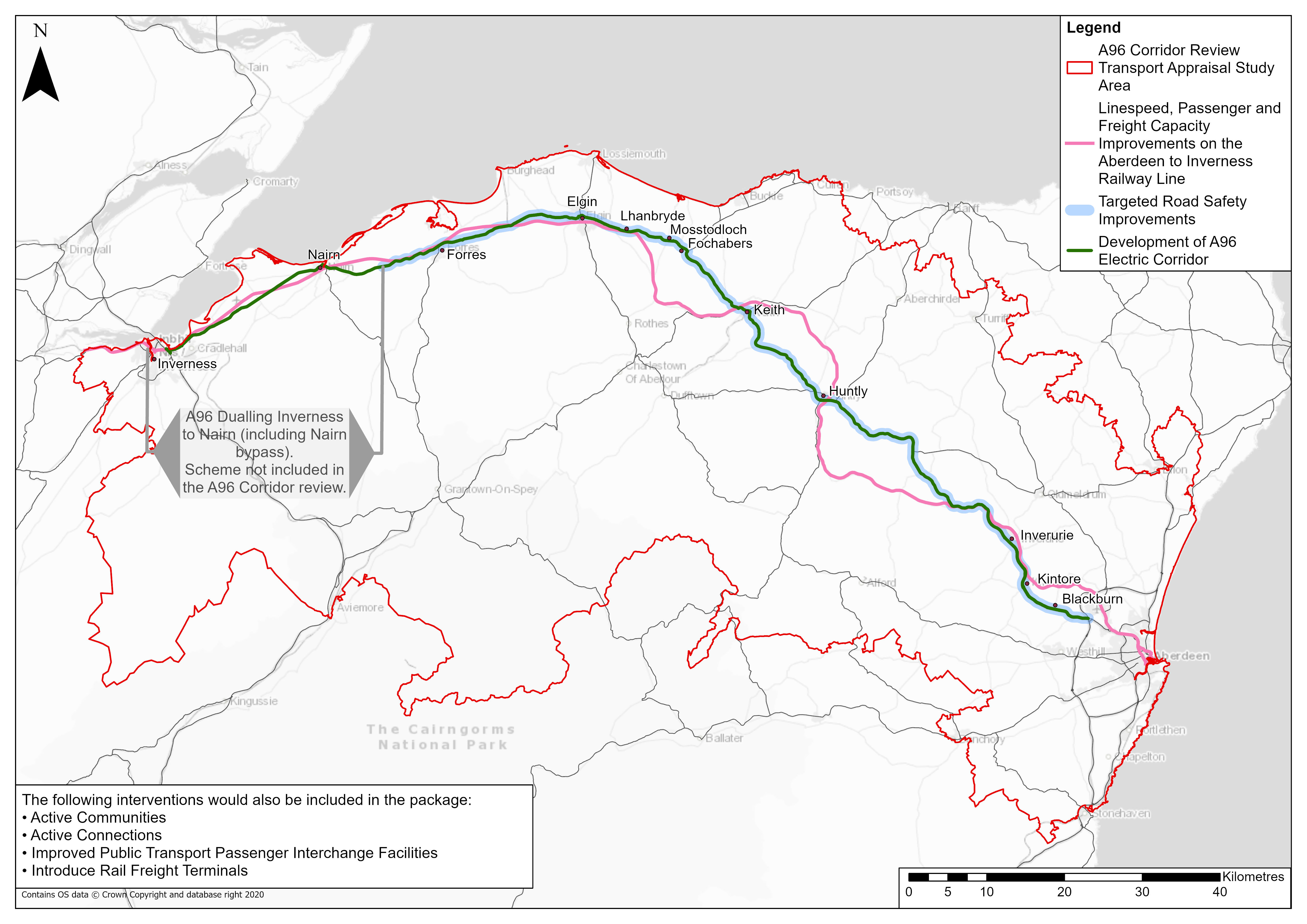

Package 2 – Potential Impacts

This package of interventions is targeted at providing network improvements to some of the less populated settlements along the A96 corridor, that are not intended to be bypassed within Package 1. The package would provide enhancements which would aim to encourage a shift to sustainable modes, increase opportunities for residents and businesses and improve road safety.

Figure 6‑3: Package 2 Extents

NaPTAT modelling observed the largest journey time accessibility benefits to key destinations and essential services in Aberdeenshire. These benefits would be linked to the rail interventions within the package and result in reduced public transport journey times between settlements along the rail line, particularly to Inverness and Aberdeen. In particular, Inverurie residents could expect a journey time reduction of between seven and twelve minutes to the nearest higher education site, benefiting 1,400 people who reside in the town and within areas where the gross household income is within the 20% lowest in the study area. Further journey time accessibility benefits in Aberdeenshire would be observed in access to employment opportunities found in Aberdeen City for residents in geographically deprived areas (20% most deprived in the country). The package would enable, on average, an additional 2,700 existing jobs located in Aberdeen City to be reached within 60 minutes using public transport from geographically deprived areas in Aberdeenshire.

Given that 48% of the most deprived households (SIMD quintile 1) do not have access to a car and are twice as likely to use the bus to travel to work as households in the least deprived three quintiles, the beneficial impacts would be highest for those from the most deprived households. However, only 6.9% of SIMD datazones within the transport appraisal study area fall into the most deprived quintile. Nevertheless, the barriers created through not having access to a car are likely to be exacerbated in communities where public transport service levels are lower. As such, the positive impact of improved public transport for socially excluded groups in these areas is likely to be greater.

Furthermore, i n the absence of viable alternatives to travel, some low-income households living along the A96 corridor may have no alternative to car ownership despite financial constraints. Therefore, there could be benefits for those groups with regards to the provision of alternative options to private vehicle use and ownership. However, this would depend on public transport fares being affordable. Moreover, if schemes delivered through the package are dependent on MaaS, it is likely to exclude certain groups without access to this technology or bank accounts, and as such this would need to be considered in the design of the schemes to ensure that they are able to benefit.

One of the alternative options expected to create benefits for socio-economically disadvantaged groups is an improved active travel environment. Including active travel interventions in conjunction with targeted road safety improvements, such as junction improvements, could aid the removal of barriers in communities through an improved sense of road safety and security for those walking, wheeling and cycling.

There is also the potential for a reduction in inequalities of health in disadvantaged and deprived communities through improved air quality at a local level. This is a result of an uptake in active travel being accompanied by reduced congestion and as a result of modal shift, which should contribute towards a reduction in traffic volumes, as shown in traffic modelling outputs.

Evidence shows that people from deprived neighbourhoods are more likely to be injured or killed as road users. Therefore, improved safety of the trunk road network could benefit those from deprived areas. However, it is acknowledged that wider factors affect road casualty rates and that more detailed assessment work is required to understand the safety benefits associated with individual schemes and how this might impact on people from deprived areas.

However, the extent to which this package would reduce inequalities of outcome for socio-economically disadvantaged groups would depend on the interventions listed being adopted, the location of the interventions, proximity to local services and the ability for those from deprived and disadvantaged communities to access the active and sustainable travel network.

The construction works associated with the interventions in this package could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Overall, this package is expected to have a minor positive impact on addressing this criterion in both ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

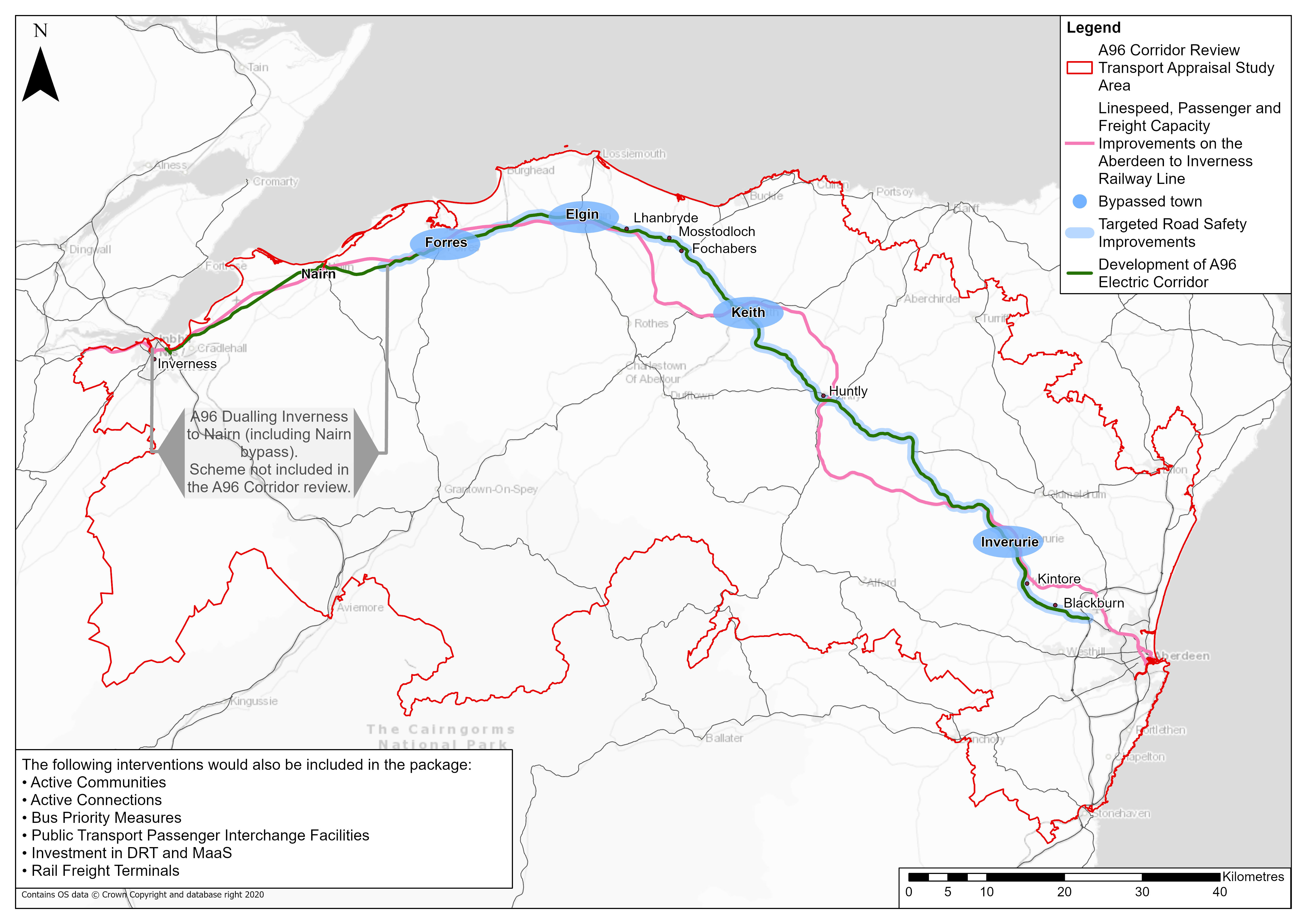

Package 3 – Potential Impacts

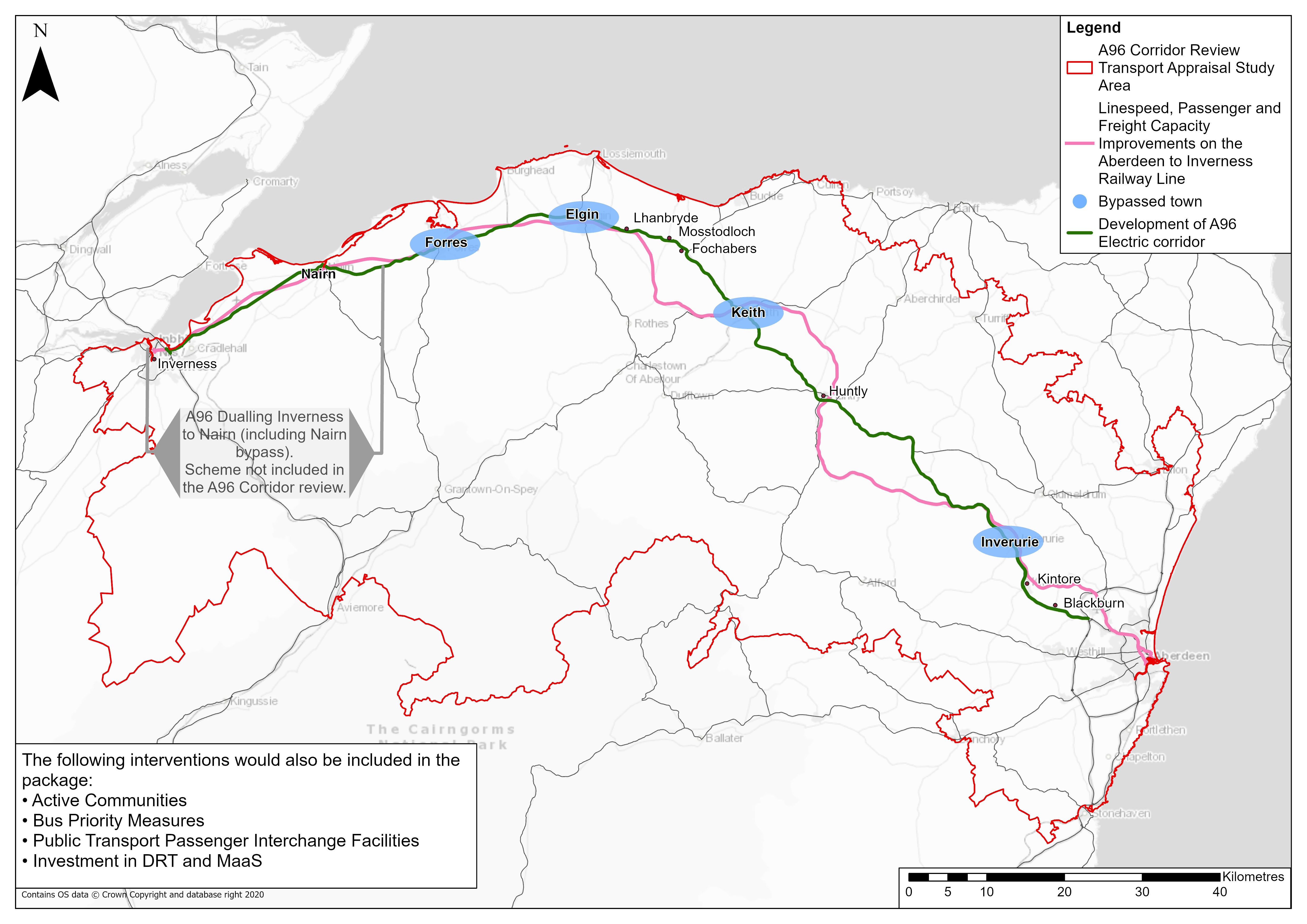

This package is focused on primarily delivering transport network improvements to rural sections along the A96 corridor by providing enhancements which would aim to encourage a shift to sustainable modes, increase active travel and public transport options and improve road safety.

Figure 6‑4: Package 3 Extents

Given that 48% of the most deprived households (SIMD quintile 1) do not have access to a car and are twice as likely to use the bus to travel to work as households in the least deprived three quintiles, the beneficial impacts are likely to be highest for those from the most deprived households. However, only 6.9% of SIMD datazones within the transport appraisal study area fall into the most deprived quintile. Nevertheless, the barriers created through not having access to a car are likely to be exacerbated in rural areas where public transport service levels are lower. As such, the positive impact of improved public transport for socially excluded groups in these areas is likely to be greater.

NaPTAT modelling observed the largest journey time accessibility benefits in Aberdeenshire, where it is anticipated an additional 150 people aged 16-24 who reside in areas where the gross household income is within the 20% lowest in the study area would be able to access the nearest higher education site within 50 minutes by public transport. Those journey time accessibility benefits would particularly be observed in Inverurie, with a journey time reduction of between six to 12 minutes to the nearest higher education site. Further journey time accessibility benefits in Aberdeenshire would be observed in access to employment opportunities found in Aberdeen City. The package would enable, on average, an additional 1,700 existing jobs to be reached within 60 minutes using public transport from Aberdeenshire for people aged 16 to 64 who reside in areas where the gross household income is within the 20% lowest in the study area. These benefits would be predominately found in Kintore, Inverurie, Kemnay and Insch (located 12 miles to the north-west of Inverurie).

Furthermore, in the absence of viable alternatives to travel, some low-income households living in rural areas may have no alternative to car ownership despite financial constraints. Therefore, there could be benefits for those groups with regards to the provision of alternative options to private vehicle use and ownership. However, this would depend on public transport fares being affordable. Moreover, if schemes delivered through the package are dependent on MaaS, it is likely to exclude certain groups without access to this technology, bank accounts or the appropriate level of support to apply for entitlement schemes, and as such this would need to be considered in the design of the schemes to ensure that they are able to benefit. Similarly, improved access to employment opportunities in Aberdeen City is identified by NaPTAT modelling, particularly across Kintore, Inverurie, Kemnay and Insch.

One of the alternative options expected to create benefits for socio-economically disadvantaged groups is an improved active travel environment. Including active travel measures in conjunction with safety measures, such as junction improvements, could aid the removal of barriers in communities through an improved sense of road safety and security for those walking, wheeling and cycling. The construction works associated with these interventions in this package could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

There is also the potential for a reduction in inequalities of health in disadvantaged and deprived communities through improved air quality at a local level. This is a result of an uptake in active travel being accompanied by reduced congestion and as a result of mode shift, which could contribute towards a reduction in traffic volumes, as shown in traffic modelling outputs.

Evidence shows that people from deprived neighbourhoods are more likely to be injured or killed as road users. Therefore, improved safety of the trunk road network could benefit those from deprived areas. However, it is acknowledged that wider factors affect road casualty rates and that more detailed assessment work is required to understand the safety benefits associated with individual schemes and how this might impact on people from deprived areas.

However, the extent to which this option would reduce inequalities of outcome for socio-economically disadvantaged groups would depend on the extent that the interventions listed are adopted, the location of the interventions, proximity to local services in rural areas and the ability for those from deprived and disadvantaged rural communities to access the active travel network.

The construction works associated with the interventions in this package could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Overall, this package is expected to have a minor positive impact on addressing this criterion in both ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

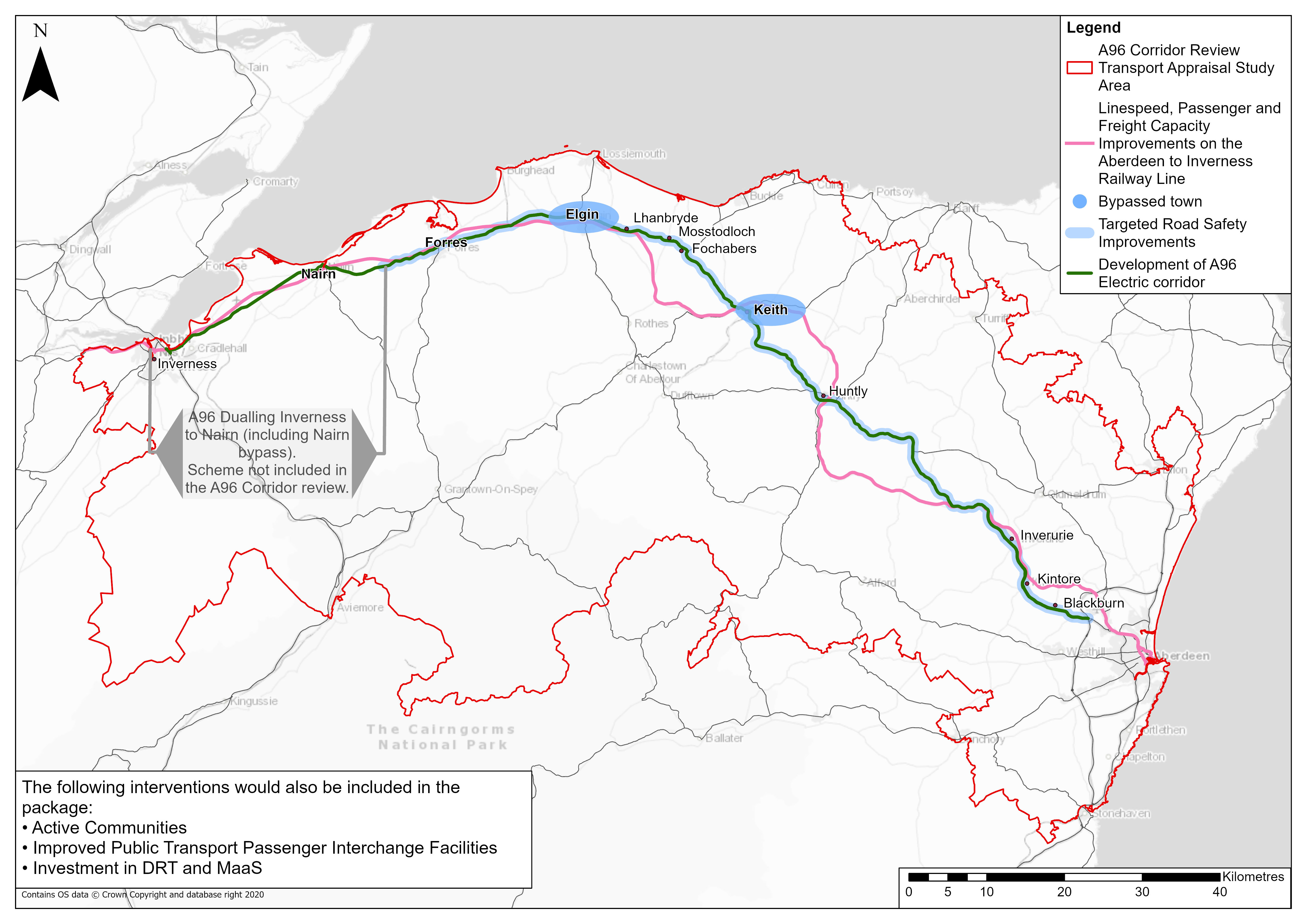

Package 4 – Potential Impacts

Figure 6‑5: Package 4 Extents

Given that 48% of the most deprived households (SIMD quintile 1) do not have access to a car and are twice as likely to use the bus to travel to work as households in the least deprived three quintiles, the beneficial impacts are likely to be highest for those from the most deprived households. However, only 6.9% of SIMD datazones within the transport appraisal study area fall into the most deprived quintile. Nevertheless, the barriers created through not having access to a car are likely to be exacerbated in communities where public transport service levels are lower. As such, the positive impact of improved public transport for socially-excluded groups in these areas is likely to be greater.

NaPTAT modelling observed the largest journey time accessibility benefits to key destinations and essential services in Aberdeenshire. These benefits would be linked to the rail interventions within the package and result in reduced public transport journey times between settlements along the rail line, particularly to Inverness and Aberdeen. In particular, Inverurie observed a journey time reduction of between six to seven minutes across most of the town in travelling to the nearest education site, benefitting 100 young people (aged 16 to 24) who reside in areas where the gross household income is within the 20% lowest in the study area. Further journey time accessibility benefits in Aberdeenshire are observed in access to employment opportunities found in Aberdeen City. The package would enable, on average, an additional 2,900 existing jobs to be reached within 60 minutes using public transport from Aberdeenshire for people aged 16 to 64 who reside in areas where the gross household income is found within the 20% lowest in the study area. These benefits would be predominately found in Kintore, Inverurie and Kemnay.

In the absence of viable alternatives to travel some low-income households living in the area may have no alternative to car ownership despite financial constraints. Therefore, there could be benefits for those groups with regards to the provision of alternative options to private vehicle use and ownership. However, this would depend on public transport fares being affordable.

One of the alternative options expected to create benefits for socio-economically disadvantaged groups is an improved active travel environment. Including active travel measures in conjunction with safety measures, such as junction improvements, could aid the removal of barriers in communities through an improved sense of road safety and security for those walking, wheeling and cycling. The construction works associated with these interventions in this package could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

There is also the potential for a reduction in inequalities of health in disadvantaged and deprived communities through improved air quality at a local level. This is a result of an uptake in active travel being accompanied by reduced congestion as a result of mode shift, which could contribute towards a reduction in traffic volumes, as shown in traffic modelling outputs.

Evidence shows that people from deprived neighbourhoods are more likely to be injured or killed as road users. Therefore, improved safety of the trunk road network could benefit those from deprived areas. However, it is acknowledged that wider factors affect road casualty rates and that more detailed assessment work is required to understand the safety benefits associated with individual schemes and how this might impact on people from deprived areas.

Rail freight is a key component of the rail sector’s contribution to Scotland’s economy. The provision of rail freight terminals is expected to enhance economic growth and private sector investment, thereby creating employment opportunities and potentially reducing socio-economic disadvantage.

However, the extent to which this package would reduce inequalities of outcome for socio-economically disadvantaged groups would depend on the extent that the interventions listed are adopted, the location of the interventions, proximity to local services, and the ability for those from deprived and disadvantaged communities to access the active travel network. As this package does not remove through traffic from communities, the potential benefits resulting from active travel interventions may be more difficult to fully realise.

The construction works associated with the interventions in this package could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Overall, this package is expected to have a minor positive impact on addressing this criterion in both ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.

Package 5 – Potential Impacts

Figure 6‑6: Package 5 Extents

NaPTAT modelling observed the largest journey time accessibility benefits to key destinations and essential services in Aberdeenshire. These benefits would be linked to the rail interventions within the package and result in reduced public transport journey times between settlements along the rail line, particularly to Inverness and Aberdeen. The package would reduce the journey time to the nearest higher education site for 300 young people aged 16-24 who reside in areas where the gross household income is within the 20% lowest in the study area. Of these, 150 young people would be able to access their nearest higher education site within approximately 60 minutes and the remaining 150 young people able to access their nearest higher education site within approximately 100 minutes. The increased accessibility of higher education sites would largely be found in rural settlements including Kemnay and Alford. Further journey time accessibility benefits in Aberdeenshire would be observed in access to employment opportunities found in Aberdeen City for residents in geographically-deprived areas (20% most deprived in the country). The package would enable, on average, an additional 3,100 existing jobs located in Aberdeen City to be reached within 60 minutes using public transport from geographically-deprived areas in Aberdeenshire.

Traffic modelling forecasts a reduction in traffic within the bypassed towns (Forres, Elgin, Keith and Inverurie) following the introduction of this package, in both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios. This is expected to create benefits for socio-economically disadvantaged groups by improving the active travel environment for those who are unable to afford a car. Including active travel interventions in conjunction with bypasses could aid the removal of barriers in communities through an improved sense of road safety and security for those walking, wheeling and cycling and the public transport interventions included within this package could encourage modal shift to more sustainable modes. There is also the potential for a reduction in inequalities of health in disadvantaged and deprived communities through improved air quality at a local level.

There is generally a heavier reliance on the use of the private car along the A96 corridor compared with the rest of the country. This is primarily due to the rural nature of the region, where there is greater dependency on the private car to access employment, education, healthcare and for social purposes. In the absence of viable alternatives, those on low incomes may have no alternative to car ownership despite financial constraints. However, there could be benefits through a reduction in journey time and improvement in journey time reliability for these drivers, providing more economical and efficient journeys.

In the absence of viable alternatives, those on low incomes may have no alternative to car ownership despite financial constraints. Therefore, there could be benefits for those groups with regards to the provision of alternative options to private vehicle use and ownership. However, this would depend on public transport fares being affordable. Moreover, if schemes delivered through the package are dependent on MaaS, it is likely to exclude certain groups without access to this technology or bank accounts, and as such this would need to be considered in the design of the schemes to ensure that they are able to benefit.

The provision of bypasses could reduce the number and severity of road traffic accidents on the sections of the existing A96 Trunk Road which route through towns. This could benefit socio-economically disadvantaged groups, as evidence shows that people from deprived areas are more likely to be killed or injured as road users. However, it is acknowledged that wider factors affect road casualty rates and that more detailed assessment work is required to understand the safety benefits associated with individual schemes and how this might impact on people from deprived areas.

Rail freight is a key component of the rail sector’s contribution to Scotland’s economy. The provision of rail freight terminals is expected to enhance economic growth and private sector investment, thereby creating employment opportunities and potentially reducing socio-economic disadvantage.

However, the extent to which this package would reduce inequalities of outcome for socio-economically disadvantaged groups would depend on the alignment of bypasses, the level to which all other listed interventions are adopted, the location of the interventions, proximity to local services, and the ability for those from deprived and disadvantaged communities to access the active travel network. It is noted that this would depend on local circumstances within each key community. This in turn would have an impact on the level of reduction of through traffic within disadvantaged and deprived communities.

The construction works associated with the interventions in this package could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Overall, this package is expected to have a minor positive impact under both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios on addressing this criterion.

Refined Package–Potential Impacts

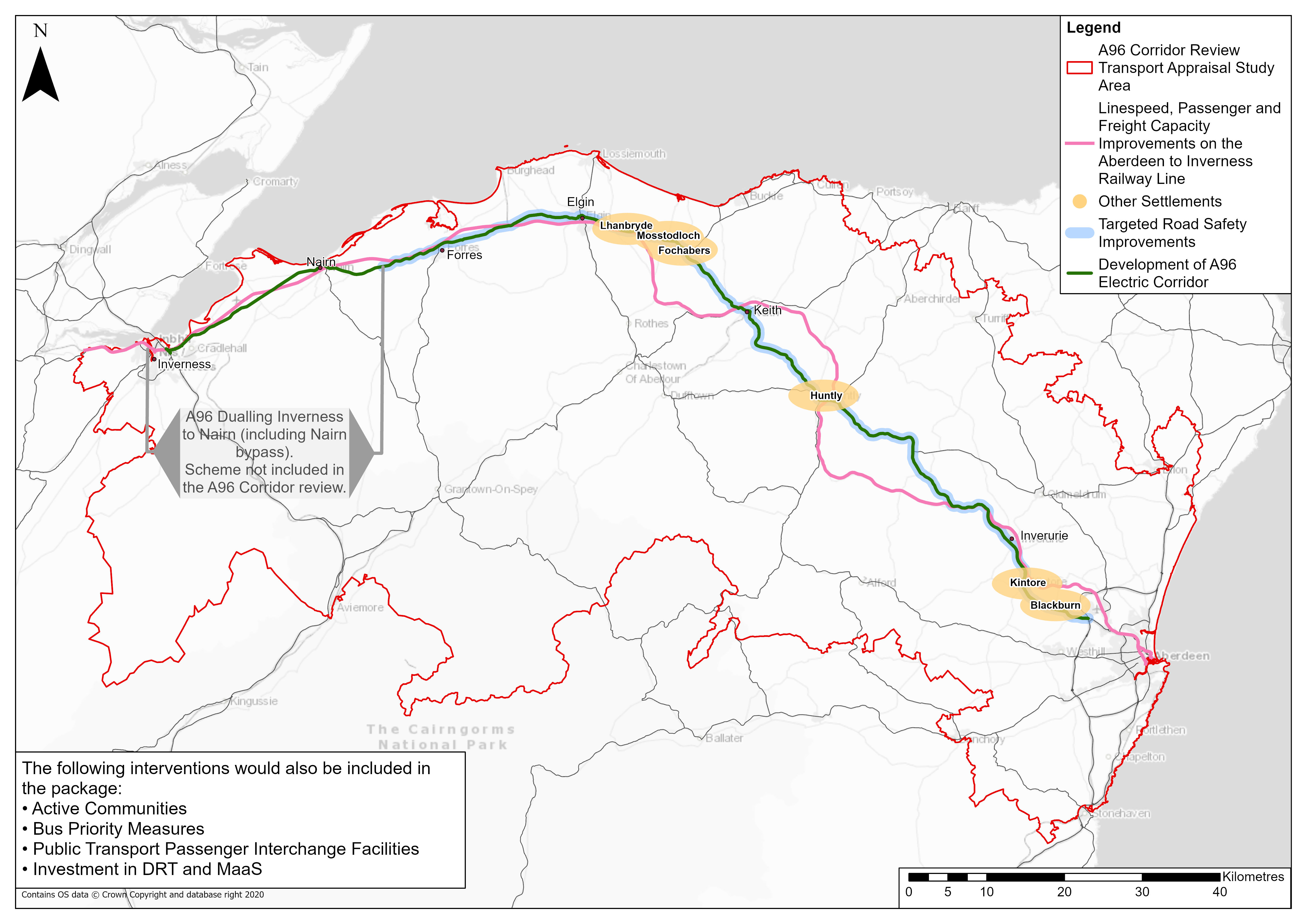

The Refined Package is focused on primarily delivering transport network improvements to both settlements and rural sections throughout the A96 corridor, by providing enhancements which would aim to encourage a shift to sustainable modes, increasing opportunities for residents and businesses and improving road safety.

Figure 6‑7: Refined Package extents

NaPTAT modelling showed journey time improvements to the nearest higher education site for young people aged 16-24 who reside in areas where the gross household income is within the 20% lowest in the study area, enabling an additional 100 people to access the nearest site within 50 minutes, a further 150 within 65 minutes, and 150 within 100 minutes. These benefits would largely be found in Inverurie, Kemnay and Alford respectively and would be expected to improve the access to education services for young people from socio-economic disadvantaged backgrounds.

The package is also shown to improve the access to employment opportunities found in Aberdeen City, whereby on average, an additional 3,800 existing jobs would be accessible within 60 minutes using public transport from Aberdeenshire for people aged 16 to 64 who reside in areas where the gross household income is found within the 20% lowest in the study area. These benefits would be predominately found in Kintore, Inverurie, Kemnay and Insch.

In the absence of viable alternatives to travel some low-income households living in the area may have no alternative to car ownership despite financial constraints. Therefore, there could be benefits for those groups with regards to the provision of alternative options to private vehicle use and ownership. However, this would depend on public transport fares being affordable. Moreover, if schemes delivered through the package are dependent on MaaS, it is likely to exclude certain groups without access to this technology or bank accounts, and as such this would need to be considered in the design of the schemes to ensure that they are able to benefit.

Traffic modelling forecasts that traffic would divert away from Elgin and Keith following the introduction of the Refined Package in both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios. This is expected to create benefits for socio-economically disadvantaged groups by improving the active travel environment for those who are unable to afford a car. Including active travel interventions in conjunction with bypasses could aid the removal of barriers in communities through an improved sense of road safety and security for those walking, wheeling and cycling. The diversion of traffic would also generate a reduction in equalities of health in disadvantaged and deprived communities through improved air quality at a local level.

The provision of bypasses could reduce the number and severity of road traffic accidents on the sections of the existing A96 Trunk Road which route through towns. This could benefit socio-economically disadvantaged groups, as evidence shows that people from deprived areas are more likely to be killed or injured as road users. However, it is acknowledged that wider factors affect road casualty rates and that more detailed assessment work is required to understand the safety benefits associated with individual schemes and how this might impact on people from deprived areas.

There is generally a heavier reliance on the use of the private car along the A96 corridor compared with the rest of the country. This is primarily due to the rural nature of the region, where there is greater dependency on the private car to access employment, education, healthcare and for social purposes. In the absence of viable alternatives to travel, those on low incomes may be ‘forced’ into car ownership despite financial constraints. However, there could be benefits through an improvement in journey times and reliability of journey times for these drivers, providing more economical and efficient journeys.

The extent to which this package would reduce inequalities of outcome for socio-economically disadvantaged groups would depend on the extent that the interventions listed are adopted, the location of the interventions, proximity to local services, and the ability for those from deprived and disadvantaged communities to access the active travel network.

The construction works associated with the interventions in this package could result in job opportunities for local communities including those from socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Overall, this package is expected to have a minor positive impact on this objective under both the ‘With Policy’ and ‘Without Policy’ scenarios.